David Beckham the footballer, was better than you probably think.

Whenever and wherever he played, he delivered.

Why is David Beckham so captivating to people?

As of writing, the recent documentary Beckham is the single most-watched English language TV series worldwide on Netflix. Since Netflix is the most popular streaming platform in the world, it’s almost certain that Beckham is the most-watched TV programme on the planet right now. But while every sports star you’ve ever heard of got a documentary after The Last Dance, the dirty truth is almost all of them were not big hits. But this one is. David Beckham is David Beckham. There aren’t many current or former sportspeople who would captivate the whole world on this level.

In football, the only living names more famous are probably Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo. Football is at a large advantage here due to its status as the world’s most popular sport. Michael Jordan and LeBron James are certainly contenders in basketball. Tiger Woods could represent golf. Novak Djokovic, Roger Federer and Serena Williams could all be tennis contenders. I’m sure you can think of others in sports I know almost nothing about.

But here’s the thing: all those other names are some of the greatest players in the history of their sport. They’ve all been recognised as the best in the world for a period of time and established their fame almost entirely on the back of this. Beckham never hit those levels on the pitch. He was a decisive player in a Manchester United team that won six Premier League titles, two FA Cups and one Champions League in the famous treble season. He never either the Professional Footballers' Association or Football Writers’ Association player of the year awards in England. He won the Manchester United fans’ player of the season award just once in 1996-97, though I would strongly argue he deserved to win it again in 1998-99 ahead of Roy Keane (don’t start me on that one). He came second on the Ballon d’Or podium in 1999, but we’re not here talking about the winner Rivaldo to this extent. Beckham’s fame outstripped his ability on the pitch. Honestly, the only comparison I can think of who did the same is Anna Kournikova.

Beckham became known to every English football fan on the 17th of August 1996 when he scored from the halfway line. I don’t know if he was actually the first to do it as is often claimed, but it was certainly the first time anyone watching in England had seen it done. Within a month, he would make his debut for the national team. Within a year, he was going out with a Spice Girl and became known to everyone in England who wasn’t a football fan as half of the most famous couple in the country. Within two years, he was a national pariah after getting sent off against Argentina at the World Cup. Within three years, he’d be a treble winner. And a little over five years after that halfway line goal, he’d score the free kick against Greece that saw England qualify for the 2002 World Cup, cementing his permanent status as a national treasure.

Beckham’s celebrity rise could’ve only happened within the media context of the late 1990s and early 2000s. The era’s tabloids and magazines are the great villains of the documentary, painted as a scourge and intrusion on the Beckhams’ lives. But there’s no question that the couple would not be as rich and famous today without such a frenzy back then. Rather than get married outside that glare, they agreed to a £1 million exclusive deal for OK! Magazine to photograph their wedding. In the modern world, driven by social rather than print media, their strategy for stardom would be impossible. The goal against Greece happened on the same day that ITV aired the first episode of Pop Idol, the original Simon Cowell series that changed the way manufactured pop music acts emerged, itself another symbol of the 2000s celebrity culture that killed off the way a group like the Spice Girls emerged. The relentless daily tabloid coverage might have been frustrating, but it surely helped build their brand enough to deliver those huge sponsorship deals with every type of product under the sun.

One of his most lucrative deals has, it must be said, been with the state of Qatar. It’s unclear just how much money he has been paid by the country in a relationship that dates back to his brief spell at Paris Saint-Germain. Qatar’s issues with human rights are well known at this point. I’m sure everyone reading this is aware of Hamas’ recent attacks on Israeli citizens and Israel’s subsequent retaliatory strikes, both of which have killed civilians. It’s notable that while Israel’s stated aim is to attack Hamas rather than ordinary Palestinians, the strikes have been in Gaza while the actual leaders of the organisation live in Qatar. That Qatar continues to avoid heavy criticism for actions such as hosting the leaders of Hamas is in part down to its ability to launder its reputation around the world, through events like the World Cup and the support from men like Beckham.

He could divide opinions among football fans. There were certainly many, not least Man Utd fans, who considered him a true great. But there were others who thought his fame massively inflated what was a pretty limited player. I was in the latter camp. Granted, I was a child, and I supported Liverpool, so I saw anything Man Utd through a deeply biased lens. To me, Beckham was a set-piece merchant totally overhyped because he was on the cover of every newspaper and magazine. To grow up in England at the time was to see him absolutely everywhere, and I was nothing if not stubborn and resentful. He was annoying to me and, therefore, he must be secretly bad at football.

But here’s the thing: I was wrong. Dead wrong. Beckham was a tremendous footballer. While he didn’t hit the heights his fame would imply, he was a superb player wrongly denigrated by football fans who didn’t like the celebrity he brought with him.

Beckham was born to play right midfield in that United team. The old-fashioned British 4-4-2 (not its more recent compact and defensive cousin) has fallen out of favour for mostly fair reasons. Modern formations tend to be about totally controlling certain zones of the pitch while “surrendering” others. An expansive 4-4-2, by contrast, gives you partial coverage everywhere. You watch those old games and there’s space all over the pitch. The passing options are all at right angles. But one thing it absolutely gives you is a lot of clear partnerships. The treble-winning United side was built on partnerships. Dwight Yorke could come short and hold the ball up while his strike partner Andy Cole ran in behind. Roy Keane offered bite in midfield while Paul Scholes provided guile (an oversimplification, yes, but you get the gist).

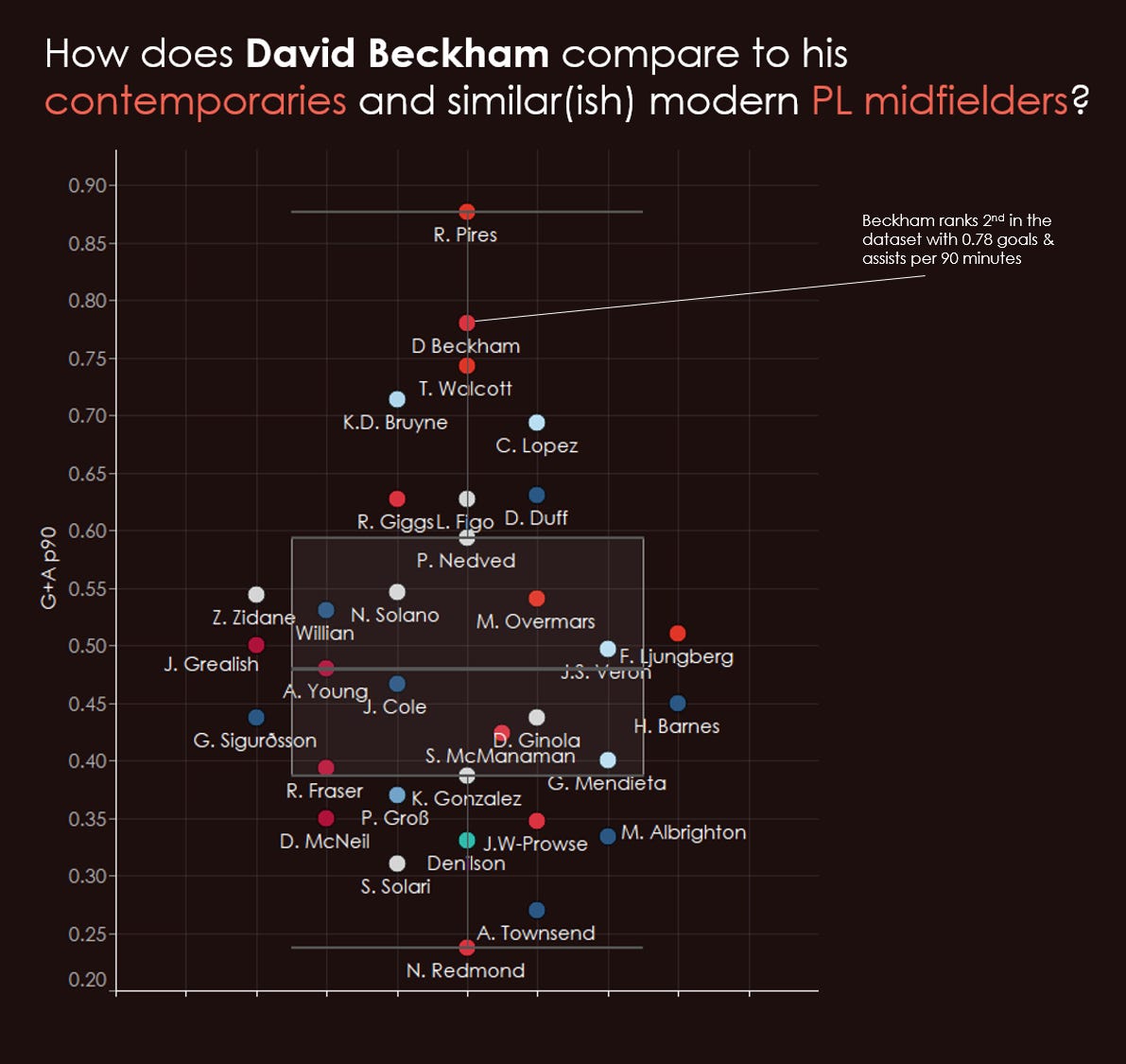

Beckham and Gary Neville, meanwhile, were an inseparable unit down the right. Neville was a more adventurous right back than remembered, getting forward and being a pretty effective crosser of the ball. He so often offered decoy runs to distract defenders and create space for Beckham’s trademark right-foot deliveries. In exchange, Beckham did all the defensive duties you could ever ask for from a wide player. He could be totally trusted to track back and protect his full back, press the players in front of him, and get up and down that right flank as much as needed. When he had the ball, we all know how well he could cross it. I haven’t seen anyone do it better. Think Trent Alexander-Arnold in those positions, but even more refined. We don’t have a lot of numbers from this era, but what we do see backs it up. As Sancho Quinn pointed out, of comparable midfielders (his subjective definition), over a three-year stretch, only Robert Pires (yes, Arsenal fans) scored or assisted more often per 90 minutes.

Yes, Scholes would become one of the finest technical midfielders in Europe… eventually. But the football of 1999 suited Beckham’s skills much better. It’s funny that the team has arguably become best remembered for its central midfield partnership when they were clearly instructed to get the ball wide as often as possible. He could offer not just a great cross, but a full range of long passing, cut backs and such high-risk, high-reward options from wide. And yes, his set pieces were quite something. The Alexander-Arnold comparison is apt. The biggest lie of the documentary is the idea he played poorly for the majority of that season after the World Cup sending-off. He was the team’s best player from the word go that season.

Of course, the 4-4-2 era was slowly coming to an end. In the two seasons after the treble, United still dominated in England. But better European sides were controlling games and dominating possession against them in the Champions League. Sir Alex Ferguson was realising that his system was flat and easy to control for sides with a third player in the centre, so it had to change. His first answer was to simply buy a really good footballer: Juan Sebastián Verón. “The [existing] midfield four played in what I would call a methodical way”, Neville later explained. “They played a disciplined role, and it was a classic 4-4-2. The way Verón played, coming out of Italy, he moved into different positions and was fluid, trying to get the ball from the left back, et cetera. He was almost the first player who broke the code. The code had to break at some point. Verón came in with that interchanging mindset, but into a team that was set into its patterns.”

Simply adding a quality player who thought differently didn’t break the code; someone had to rewrite it. That person was Carlos Queiroz, hired as Ferguson’s assistant in 2001. Queiroz brought continental ideas to a very British club. He knew that football was becoming more fluid and wanted United to play with rapid counter attacks. He saw that Beckham’s previous extreme energy levels were beginning to dip. In the documentary, Queiroz bizarrely puts this down to the physique he built up for an advert. In Ferguson’s autobiography, he blames Beckham’s celebrity status for turning the player’s head, and wonders if “he was starting to think he no longer needed to track back and chase”. My guess is that it was about fitness. Beckham famously broke a metatarsal bone in his left foot on the 10th April 2002, less than two months before England’s first World Cup match in Japan. “If the fracture is undisplaced”, Professor Angus Wallace, professor of orthopaedic and accident surgery at the University of Nottingham claimed at that time, “the treatment is a cast for four to six weeks, and then return to training, which will take a further two to four weeks of rehab”. He was said to have recovered from the injury after four weeks, then started all but one match of England’s World Cup campaign seven weeks after the injury. He pushed the limits of his recovery timeline and then went straight into a gruelling tournament. It shouldn’t be a shock if he was less than 100% fit the following season.

But Ferguson decided it was time to change the team. The future was fast and interchanging wide players who were more likely to come inside and score than put in a cross. He decided Cristiano Ronaldo was the player to replace Beckham who, in all fairness to the lad, had a decent career. But I can’t help wondering if there was still room for Beckham in this team. What if he moved inside and played as a central midfielder orchestrating the play by pinging passes around? Yes, he would need to rein in his instincts to make every pass a “Hollywood ball”. But could he have adapted? Ferguson knew he needed a deeper midfielder who could knit things together with smart passing. He didn’t truly have that player until Michael Carrick arrived in 2006. Could Beckham have been the answer?

If United increasingly didn’t suit him then Real Madrid definitely didn’t suit him. Beckham had a very strictly defined role at Old Trafford. As Neville said, United played in a “methodical” way. Players stayed within their zones. Beckham would be glued to the right flank, Ryan Giggs would do similarly on the left, while Scholes and Keane stayed in the middle. They didn’t swap when they felt like it. I would argue this was a primitive version of what we now call “positional play”. Madrid was the opposite. It was a club where individuals had the freedom to make decisions for themselves. United had a plan for creating space, even if that plan was just a basic “get it wide” instruction. Madrid weren’t that strict or clear. Individuals were often expected to figure problems out themselves. United simplified Beckham’s game, which both helped and hindered him. At the Estadio Santiago Bernabéu, it wouldn’t be so straightforward.

Signing Beckham became infamous as the moment when Florentino Pérez’ galácticos vision fell apart. In Beckham’s first three years, Madrid did not win a single trophy outside the Supercopa de España. The club went through five different managers and two presidents as the whole sporting project crumbled. Beckham became a symbol for this decay, but he was hardly the root cause. In his first season at the Bernabéu, the first major galáctico Luís Figo already had Beckham’s preferred right-wing locked down but, at age 31, had looked like he peaked a few years earlier. Zinedine Zidane, the big arrival of 2001, was also 31 years old and looking short of his Juventus-era peak. 2002’s galáctico, Ronaldo Nazário, pulled off one of the biggest miracles in the history of football, picking up an injury doctors said would stop him ever playing again to win the World Cup as top scorer. But that incredible narrative is exactly why Madrid shouldn’t have signed him straight after his Seleção heroics; he never came back the same player. All three players recognised they were declining physically, and each responded by limiting their game to focus on their core attacking strengths, doing less defensive work in the process.

Figo, Zidane, Ronaldo and local favourite Raúl were well-established as the front four, leaving only space in central midfield. Everyone talks about the decision to sell Claude Makélélé the same summer Beckham arrived. “Why put another layer of gold paint on the Bentley when you are losing the entire engine?” goes the quote attributed to Zidane. Personally, I can’t help but wonder how good they’d be together in the same midfield. Beckham often played next to Iván Helguera (a natural centre back pushed up into midfield) in the bigger games, while Real would employ a “fuck it, we’re Madrid” approach against smaller teams and put him next to Guti. Beckham might not have been the most patient deep-lying playmaker. He has the tactical brain of a Roy-of-the-Rovers Englishman looking to get it forward quickly. Beckham may not have pausa, that ability to put one’s foot over the ball, slow things down, and wait for the moment to arrive that’s so prized in Spanish-speaking football cultures. He would sometimes vacate his position and open up a hole in Madrid’s midfield. But he was excellent at starting attacks and forcing play from deep. He could open up games in an instant with his passing range. He was almost exactly the player Ferguson signed Verón to be.

Real Madrid hired Fabio Capello in 2006 to turn around a disastrous run of three years without a trophy. He started Beckham in the first two league matches, the second actually coming after the infamous incident when he was late for training, and the first Champions League game. In the middle of all this, England’s new manager Steve McClaren decided he wanted to show everyone he was the man by dropping Beckham from the squad entirely (another surprising omission from the documentary). That seemed to hurt him badly. “He was very upset at not being in the national team”, Capello claimed, as part of the reason he lost his Madrid place, starting just four times in all competitions between mid-September and Christmas. All of this came right in the last year of his contract and, by the time January came around, he was free to negotiate with other clubs. His star had fallen so far and so fast that he was seriously linked with Bolton Wanderers. He signed for LA Galaxy and was immediately told by Capello that he would not play for Real for the rest of the season.

After coming under pressure within the dressing room, Capello reversed that decision within a month and Beckham did more than enough to change his mind. The Italian wanted Beckham to roll back the years and play in his old right midfield role. And despite everything, despite the fact that he was 31, that Ferguson and Queiroz decided he didn’t have the legs and effort for that position four years earlier, that England deemed him worse than Aaron Lennon and Shaun Wright-Phillips, that “no other technical staff in the world wanted him except Los Angeles” according to Real president Ramón Calderón, he was superb. “He has now recovered his best physical and psychological form”, Capello explained. “He is a great player and is now playing as he did when he was at Manchester United”.

Had he waited until the end of the season to sign a contract, he would’ve had his pick of top European clubs along with an offer to renew at Real. But the deed was done and he was going to America. He had planned for semi-retirement before realising he still had plenty left in the tank. Capello was managing England by 2008 and recognised what Beckham still had to offer. The path was clear to Beckham: to play for England at the 2010 World Cup, he needed to be playing in Europe, despite his big MLS contract having years left to run. He found a compromise by agreeing to a six-month loan move to AC Milan in January 2009. There were sceptics in Milan viewing it as a marketing move (and perhaps Capello called in a favour from his old friend Silvio Berlusconi).

Milan were managed by Carlo Ancelotti, the king of finding a role in the team for big stars and making it work. Beckham slotted in on the right of Milan’s midfield diamond, with the freedom to drift out wide and put crosses in but without needing to run up and down the flank like he once could. For all Real Madrid’s hype, that Milan side might have a claim to being the true Galácticos, with Beckham playing alongside Paolo Maldini, Andrea Pirlo, Clarence Seedorf, Kaká and Ronaldinho. Beckham had no trouble getting into the team, starting 18 of Milan’s remaining 20 Serie A matches. He was perfect for what he was being asked to do, drifting wide and forming a really good understanding with Alexandre Pato. With so many other threats to deal with, teams offered him far too much space to work wonders with that right foot. “He probably has given a superior contribution to what we expected”, Ancelotti said. No one could quite believe that Beckham was still more than able to be decisive at the top level.

That was largely the end. He made another loan to Milan in 2010, but a bad injury stopped him from contributing to the same extent and ruled him out of that year’s World Cup. It’s hard to come back from injury at age 34. He returned to MLS and saw out his contract, before retiring at what really was a marketing move this time at Paris Saint-Germain. That doesn’t change that he was far better in the second half of his career than most remember or expected. Football people instinctively distrust anyone who courts celebrity like Beckham, but his contributions on the pitch were unimpeachable throughout his career.

He should’ve won more after leaving United. From 2003 onwards, he won one La Liga title, a Supercopa de España at Real Madrid, two MLS Cups and two Supporters’ Shields at LA Galaxy, and a Ligue 1 title that barely counts because he only played 315 minutes. He should’ve won at least one more major trophy at Real Madrid, and he should’ve then moved to another top European club instead of LA Galaxy to mount a serious aim at big honours. But the football he played is pretty consistently excellent. I don’t think Ferguson regrets selling Beckham, but perhaps he should. I’ve no doubt in my mind he could’ve achieved as much in his later years at Old Trafford as Giggs or Scholes. Beckham might be a celebrity footballer. He might be a bigger brand off the pitch than on it. But that should never make anyone doubt his playing talent. Beckham is one of the best footballers England have produced in the last 30 years. I won’t hear anything said otherwise.

Whilst Beckham might have been able to play at a higher level than MLS after leaving Madrid, the right to buy an expansion team at a discount was an incredible bit of negotiation from him and his advisors. I doubt anything as valuable would have been on offer from other teams, even if he had waited until the end of season.

I was a kid for Beckham's early years but I watched a lot of MLS and then a lot of clips afterward of his old stuff. His quality was clear, and like the majority of the near-retirement legends that came over, he was in another class in the US. I appreciate that he didn't think he was too good for the more workman like aspects of MLS and helped rebuild that Galaxy team that was quite terrible when he arrived. Agree, he was better than just the trophy haul.