Mikel Arteta is the great British manager of his generation

Fabio Capello had a problem.

His England team had looked nowhere near good enough at the 2010 World Cup. After being hired to be the great saviour of English football, he was suddenly lucky to stay in the job. The Three Lions were short in many areas, but compared to champions Spain, it really stood out how poor they were at keeping hold of possession in midfield. They seemed to lack that sort of technical passer in the middle to keep things ticking over. They needed to get a little more Spanish.

The answer, as it seemed, was right there. Everton midfielder Mikel Arteta was impressing in the Premier League with exactly those qualities. Though he was born in San Sebastián, he had lived in the country long enough to earn a UK passport and, theoretically, play for England. Capello was reportedly interested, as was the player. “I would have done it”, Arteta said many years later. “I feel very proud about it.

“I look English, I’ve been here so long. I’ll tell you right now, the feeling I have, for me this is like home. I’ve been here for 22 years.”

As it was, Arteta had been capped by Spain at Under-16 to Under-21 level. This in itself does not stop a senior player from switching countries, but these appearances came long before he was eligible for England, which FIFA states is reason to deny him the right to switch. Arteta never did get the chance to play at senior international level.

No English manager has ever won the Premier League. The way things are going, that doesn’t look likely to change any time soon. Unless.

English football likes to brand itself as “fast”, “intense”, and even “physical”. There is some truth to that, but if we’re being honest, it’s not really a cohesive identity anymore. If you watch the Bundesliga, La Liga or Serie A, you can see plenty of distinctly German, Spanish or Italian football. Those leagues are dominated by managers native to said countries, who share a certain tactical identity that has been shaped by a national “way of playing”. The same can’t be said in England. Most managers are hired from abroad, and even the few domestic coaches aren’t particularly wed to a philosophy. Other than nationality, there is nothing particularly linking the way Sean Dyche, Eddie Howe and Scott Parker play football. It’s a mish-mash. The Premier League’s strength has been exactly that. It has outperformed other leagues by importing the best talent and being open to all sorts of different ideas. As strange as it sounds, this isn’t as new as you might think.

Before England poached top talent from continental Europe, it did so from another foreign land: Scotland. Nine managers have won the English top flight at least four times. Of those nine, five (Alex Ferguson, George Ramsay, Matt Busby, Frank Watt and Kenny Dalglish) are Scots. One other is Catalan (take a guess which one). That leaves just three Englishmen to achieve the feat: Bob Paisley, Tom Watson and Herbert Chapman. Of the three, Paisley is the only one to win after the Second World War, and he was arguably building on the success of another Scot, Bill Shankly. Scots have consistently shaped the way the English play football.

It was in Scotland where the short passing game was first celebrated, while in England the “manly” way to play was to keep your head down and dribble. Scotland was the engine for ideas in the early history of football, so it made perfect sense that the country would develop a strong tradition of managers, of which many of the best would move south.

Alex McLeish is not one of the best. But he had his eye on the ball when he signed Arteta at Rangers in 2002. At this point, Arteta had spent his career at Barcelona (failing to reach the first team) and Paris Saint-Germain. Scottish football might’ve been a shock to the system, but it’s one he adapted to well before heading back to Spain to sign for Real Sociedad. That lasted six months before another Scot, David Moyes, brought him to the Premier League.

Moyes, as you know, has his way of playing. Arteta was a pivote in Spain, playing as a passer to build play just in front of the back four. Moyes, however, used him as the more creative central midfielder next to a destroyer. Everton were compact and disciplined, playing two banks of four and prizing solidity above all else. Training sessions must have involved a lot of work on team shape without the ball. They weren’t a long ball team to the extent of Sam Allardyce or Tony Pulis’ sides, but they were direct and physical. Arteta was the exception, the spark of variety in a team with Tim Cahill and Marouane Fellaini.

Moyes’ first spell at Everton was all about the long, hard grind of working on predictable patterns in training, with and without the ball. It was tough, it was boring, and it was unglamorous, but it gradually and consistently improved the team.

Everton didn’t have the money to keep their best players forever, so Arteta was sold to Arsenal in 2011. This was a very different football club under a very different manager. Moyes was about discipline and structure in every sense, on and off the pitch. Arsène Wenger, conversely, is the most laissez-faire manager I can remember seeing at the very top.

During his first season at the Emirates, he played as the more creative midfielder in a double pivot next to Alexandre Song. 12 months later, Song left for Barcelona, and Arteta now returned to his pivote role, frequently playing as the more reserved midfielder next to Aaron Ramsey or Jack Wilshere. This really summed up the differences in priorities: Arteta’s job was to distribute the ball to players better than him in the final third. He wasn’t the source of variety anymore. He was at the expected standard in terms of technical ability, passing it to real wizards like Santi Cazorla and Mesut Özil.

Arteta played regularly for three seasons at Arsenal, eventually becoming the club captain but playing much less in his final two years before retiring in 2016. Everyone expected him to go into management at some point, and he landed the dream apprenticeship as Pep Guardiola’s assistant at Manchester City.

There was a time when most of us thought of Wenger and Guardiola as being fairly similar. They both liked to play good football built around a short passing game. It’s funny how much the dividing lines have changed, because now they almost feel like polar opposites. Whereas Wenger focused on building an environment where players could express themselves with freedom on the pitch, Guardiola is an obsessive when it comes to structure, with and without the ball.

Arteta spent time at La Masia learning the basics of Barcelona’s positional play, but I don’t think that’s why Guardiola hired him. Guardiola doesn’t need help with that because he’s already the world’s number one expert at coaching it. But I think what Guardiola did need is someone who had lived in both worlds, who understood positional play and the Premier League. Guardiola often mentions the anecdote that Xabi Alonso (a player of his at Bayern) told him that he’d have to adapt to defending second balls in England, something he’d never previously given much thought. Arteta had thought about second balls.

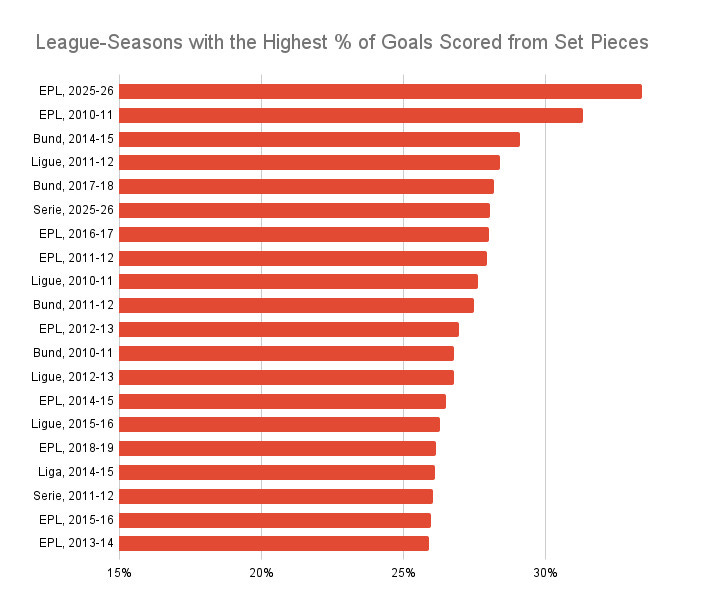

And so he has demonstrated at Arsenal. There are absolutely elements of positional play in Arteta’s football. I don’t think we can doubt that a lot of the structure comes from there. At the same time, everyone knows how much Arsenal use set pieces. No one in Spain does that. Here’s a fun graph from friend of the newsletter Michael Caley, looking at the percentage of goals scored from set pieces, by individual season in each of Europe’s top five leagues. This year’s Premier League campaign leads the way. La Liga has just one of the top 20 places, from a season that took place over a decade ago.

I don’t want to suggest that Spanish football is exciting and technical while English football is physical and boring, because I don’t think that’s true. “Positional play” is essentially a Dutch idea reinterpreted as part of a Catalan natonalist project. It’s not really that “Spanish”. Spain has more than its fair share of reactive managers, focusing more on countering the opposition than developing their own game. Unai Emery is probably the best practitioner of this style right now. I’ve always felt that the typical Spanish manager is less like Guardiola and more like Rafa Benítez.

But it’s different to the British version. Anyone who watched Merseyside football in the 2000s could tell you that. In words that would later haunt him, Benítez called Everton a “small club” in 2007, after Moyes’ side successfully earned a 0-0 draw by parking the bus at Anfield. The Spanish version of this would probably be to stifle the opposition by playing a little higher up the pitch, making more fouls to break up the play, focusing a lot less on long balls and set pieces. It’s a different flavour of vomit. When Arteta’s Arsenal produce some of the worst 1-0 wins you’ve ever watched, they do it the British way.

Arteta might be the ultimate product of the Premier League. He’s a Basque-born former player who learned a mix of Scottish and Catalan ideas about football while in England. It could only happen here. Arteta is the result of a footballing culture more cosmopolitan than elsewhere. English football has been in an identity crisis for a long time now, ever since pundits on TV started complaining about the number of foreign players and managers. But what if this is who we are now? What if Arteta, an immigrant long settled in the country, best represents what the Premier League is about?

I can’t think of a single more “Premier League” manager than him. And for that, maybe he deserves to win the title this season.