Pep in the Knockouts: Part Three

Citeh

Note: this is part three of a four part series on Pep Guardiola’s successes and failures in the Champions League. Please read the introduction for more information.

This feature is entirely free, but I can only produce this work with your support, so I’ve launched a paid tier. You can read more about that here. Please consider subscribing if you can afford it.

It was probably inevitable that Pep Guardiola would work in the Premier League at some point, and Manchester City were always the favourites to get him due to Txiki Begiristain’s time at Barcelona, but he picked a hell of a moment to come to these shores.

English football’s respect for Guardiola’s Barca and Bayern sides was always begrudging. Everyone knows that patient passing and possession is not, shall we say, the English way, but the distrust of this is so deep rooted as to be verging on a disease. Even an ex-player as thoughtful and reflective as Gary Neville spent the first leg against Real Madrid in 2014 decrying the side’s lack of “cutting edge” as the club became more possession dominant under Guardiola compared to the slightly more reactive Heynckes side. After the second leg, it seemed as though English football could barely sustain its glee that he’d been outdone by a fast counter attacking team. That’s good football, not this passing shite we’ve been stuck with for the last few years.

If there was a whiff of xenophobia in the subtext, it was about to very quickly become text. Leicester City won the Premier League through one of the sport’s greatest ever upsets in 2015/16 and, at least in the English footballing public’s eyes, they did it our way. Leicester played 4-4-2, started the same team every week, and kept it simple with direct counter-attacking football. It was the opposite of Guardiola. That the shape was really more of a 4-2-3-1 as Shinji Okazaki dropped deep didn’t matter to the narrative. That Claudio Ranieri specifically adapted his approach to this in order to suit his environment in a way that only an Italian manager schooled at Coverciano could was a fact hardly anyone in England even knew. Those were expert opinions, and people in this country have had quite enough of experts.

Yes, Guardiola arrived in Brexit Britain as the avatar of continental cosmopolitanism. People in this country really wanted him to fail this time and show that our league is the hardest. He’s got to go to the Premier League and get something, and I’ll tell you what, English football would love it if we beat them. For a brief moment, it looked like it was happening.

In his first season at Man City, Guardiola faced problems on a scale he’d never before dealt with. During his first year in charge of Barcelona, the new manager had a number of players who were a fair bit short of “world class”, but they overwhelmingly understood exactly how he wanted to play, having learnt at the Catalan cathedral of positional play. At Bayern, he inherited a squad that had little to no idea of how to play Guardiola’s football, but they had astonishing strength in every position. That was more than enough to win almost every match while he taught them to play the game his way. Both times, he had enough to do what he needed.

(I believe I first heard this point made by The Double Pivot Podcast’s Mike Goodman (my former editor at StatsBomb), but I can’t find that in the bowels of the internet, so you’ll just have to take my word for it.)

At the Etihad Stadium, he had neither. City’s style of football under Manuel Pellegrini was “attacking”, yes, and “possession-focused”, but it lacked a clear structure. Pellegrini has always been best at finding ways to help talented individuals thrive (part of why he’s no longer a top coach), whereas Guardiola is all about the system and having a clear plan in and out of possession. There was always thus going to be a learning curve, but it wasn’t helped by City’s poor recruitment in the years leading up to the Catalan’s appointment. City are an extraordinarily wealthy club, but millions were squandered on older players who didn’t offer a lot by the time Guardiola arrived.

Around halfway through the season, you could see that the attack was beginning to form. Raheem Sterling and Leroy Sané played as a sort of rich man’s version of the Douglas Costa and Kingsley Coman pair, as Guardiola continued to use wingers stretched very wide on their stronger footed sides. Kevin De Bruyne and David Silva were nominally central midfielders in a 4-3-3, but the pair pushed very high up the pitch to become almost dual number tens, constantly finding Sterling and Sané with their incisive passing. Gabriel Jesus’ injury meant that Sergio Agüero led the line. You could already see the patterns of cut backs towards the centre of the box for tap ins that would dominate the side through their two Premier League title wins.

The defence, however, was a great big mess. Part of this comes from what’s in front of them. Pressing systems take time to coach, and the City attackers were still learning where to be to prevent the ball from getting into their own half in the first place. But a lot of it was on the individuals. John Stones was the marquee signing to rebuild the back four that summer, and I can’t think of a more damning statement than that. Vincent Kompany’s frequent injuries meant he was frequently partnered by the just as chaotic Nicolás Otamendi. His full back options of Pablo Zabaleta, Bacary Sagna, Aleksandar Kolarov and Gael Clichy all felt done at the highest level by this point. In front of them, Fernandinho was a reliable defensive midfielder, but Guardiola often rolled back the years and put Yaya Touré, who at this point could not turn quickly to save his life, in the pivote role instead. Claudio Bravo had been a disaster in goal and lost his place to Willy Caballero. It stunk.

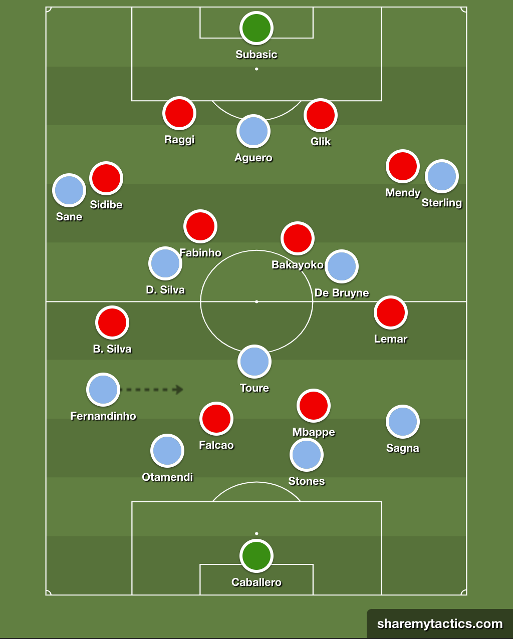

In the round of 16 this season, City were facing a Monaco side primarily good on, yep you guessed it, attacking transitions. There was something delightfully old school about the way Leonardo Jardim set up with a compact 4-4-2 based on counter attacks. Upfront he had two genuine top goalscorers: a Radamel Falcao rolling back the years and a Kylian Mbappé just starting to go supernova. Wide men Bernardo Silva and Thomas Lemar would come inside to provide the guile, while full backs Benjamin Mendy and Djibril Sidibé would fill the space on the overlap. Central midfielders Fabinho and Tiémoué Bakayoko would play dynamic box-to-box roles, both covering the centre backs and still offering a threat going forward. It was a little open at times, but very exciting and very fast.

Guardiola went into the first leg against Monaco at the Etihad doing something that may surprise you: he pretty much just picked his best team. The attack was, as I just explained, the attack that started the game. Stones and Otamendi played together in front of Caballero, with Sagna selected at right back. Due to injury problems, Fernandinho was forced to play left back, but in an inverted fashion, often ending up partnering Touré in midfield. The Monaco side was as expected.

With both teams really clicking in attack to cover a shaky defence, a thriller was on the cards. And we got a 5-3 classic, with continual fast breaks leading to goals. It was notable just how poor City’s defensive core was, not just at “defending” but also in possession. We associate Guardiola teams with a crispness in playing out from the goalkeeper, and they were certainly trying to do that. But indecisiveness, poor understanding, and simply poor quality led to the side playing their way into trouble time and time again. It was a good example of how “playing out from the back” is as much about how you do it as whether you do it or not. City and Monaco both played some dazzling football at times while leaving themselves open, and the 5-3 weirdly felt like a fair result, as City got the actual lead while Monaco took back three away goals.

Guardiola changed his defensive personnel for the second leg, but the approach was broadly the same. Kolarov started at centre back alongside Stones, with Clichy at left back and Sagna on the right. Fernandinho played at the base of midfield, and in front of him it was all the same. Falcao was injured for Monaco, so Valère Germain did a workmanlike job in his place.

The first half of the second leg at the Stade Louis II was as poor as I’ve seen a Guardiola team play in the Champions League. Monaco sat deep in their 4-4-2 shape and it was as though City had never seen a team do that. If you’re playing Premier League football every week, you really shouldn’t get flummoxed by a physical side defending deep, but that’s what happened. Monaco weren’t even doing anything innovative beyond sitting back and hitting City on the counter. They outshot Guardiola’s team 6-0 in that 45 minutes. No shots! For a Guardiola team! I wish I had some clever tactical explanation here, but City were just so flat for no clear reason. Monaco were 2-0 up at half-time, about to go through on away goals, and there was no question that they deserved to be there.

City did improve significantly in the second half, taking 6 shots to Monaco’s 2. They were moving the ball from David Silva and De Bruyne to the wide men much more freely and getting into their usual patterns. City did about enough to get ahead again via Sané, and just needed to switch on and defend set pieces properly thereafter. That didn’t happen. After creating nothing of note in open play after half time, Monaco get a wide free kick that goes straight to Bakayoko’s head for him to fire it home. Just control the game once you’re ahead. Slow it down. Don’t give cheap free kicks away when you know the opposition are bigger and stronger than you in the air. Keep the ball. City couldn’t do that, and they paid the price.

The xG has the tie almost exactly level if you take out Falcao’s missed penalty. This was a wild encounter from a City side that lacked the ability to control football matches. That would come, so it’s hard for me to put this into the narrative too much. 2016/17 was the one time when Guardiola’s team weren’t realistically among the Champions League favourites, and it felt like Monaco just had a bit more about them. It was a pilot for a series that would deliver the Premier League twice, but this competition gets a little more dicey.

City improved a lot in the subsequent year. A lot a lot. After nabbing Bernardo Silva and Benjamin Mendy from that Monaco side, City then added right backs Kyle Walker and Danilo, goalkeeper Ederson, and eventually left sided centre back Aymeric Laporte. But the biggest gains came from simply understanding Guardiola’s system better. This was a complete side that was able to dominate Premier League games with alarming frequency. It was a year behind schedule, but the revolution had arrived in Manchester.

Guardiola’s time in England was supposed to be about the Manchester Derby. A certain José Mourinho had turned up at Manchester United, and the Premier League was supposed to rekindle the pair’s clash with the backdrop of a slightly dormant local rivalry suddenly set alight. United finished second in 2017/18, but the title race was never really on, and Mourinho was getting ready to implode once more. But, about 30 miles down the M62, something else was coming. Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool were about to click into place.

The 2017/18 vintage Liverpool that faced City in the Champions League quarter finals was not as complete a side as the one in subsequent seasons. Klopp hadn’t quite developed a clear way of beating lesser sides through heavy use of the full backs. Loris Karius was in goal. But in some ways it was more explosive, as a pre-injury Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain pushed up to support Sadio Mané, Roberto Firmino and an exploding Mohamed Salah. This was a side that looked to force counter-pressing opportunities then burst forward with electric pace. It was Mourinho’s Inter from the first leg at the San Siro, but on steroids.

Since this was another Premier League team, they were hardly unknown to Guardiola. City won in a 5-0 rout at the Etihad that season, but a Mané red card just before half time made it much easier to dominate. More recently, City lost a 4-3 thriller away at Anfield, with Liverpool breaking the press with ease and forcing a number of good chances against City’s soft underbelly. This was going to be hard.

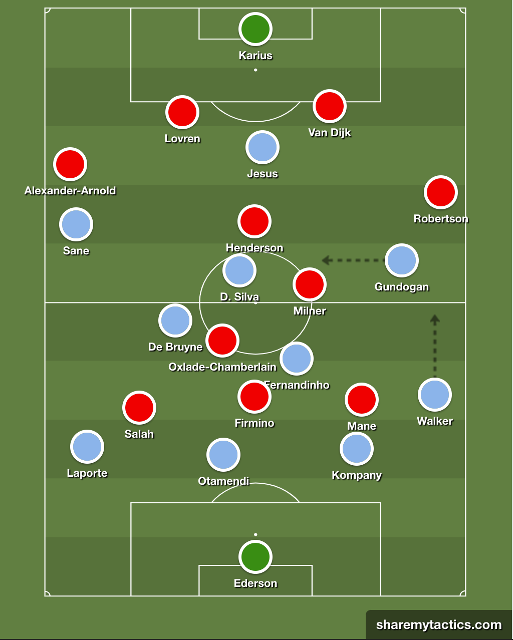

The big tactical choice from Guardiola was to bench Sterling and start Ilkay Gündoğan on the right. Perhaps Sterling’s previous difficulties returning to his former club’s ground played an impact, but there was a clear tactical plan here. He could’ve started Bernardo Silva on the right, but instead he went for a true central midfielder. Gündoğan took up a very narrow role to come inside, giving City a numerical advantage in central midfield, letting four passers circulate the ball to, ideally, prevent counter attacks from launching. To fill the space on the right, Walker played more aggressively than usual. This meant that City would have a better ability to slow the game down and prevent rapid transitions, but when those moments came, they’d be three against three with Liverpool’s attackers. Jesus over Agüero was the only other choice of note. Klopp started James Milner over Gini Wijnaldum, and Dejan Lovren was selected with Joel Matip out, but otherwise played exactly his expected team.

Liverpool scored three goals in the first half-hour and all but won the tie there and then. City did get caught a little unfortunate with Oxlade-Chamberlain’s long range strike, but there’s no question they were poor in the first half at Anfield. The apparent plan to circulate the ball through midfield and prevent counter-pressing opportunities just failed completely. Liverpool just pressed those midfielders whenever they had the ball and won it easily to get straight through on goal. I don’t know why this was so poor, but it was genuinely shocking to see a Guardiola team so easily give the ball away. And since he then structured the team to only leave three defenders behind, Liverpool then found it easy to break through. Once again, Guardiola was convinced the way to stop a counter was at the source rather than once it happens. But the best sides in attacking transitions will force them to happen at least some of the time.

Sterling replaced Gündoğan after an hour, which felt like an admittance that Guardiola’s tactical plan didn’t work. As much as the issue was about the structure of the team, it must be said that Gündoğan had a really poor evening, passing calmly but offering Robertson far too much space to attack into, both because he was instructed to play narrow and as the Liverpool left back had such an athleticism advantage. He’s more of a risky passer, so that was presumably Guardiola’s rationale, but it does seem like Bernardo Silva would’ve performed the same tactical role much better. Gündoğan and De Bruyne had actually swapped positions for a period, allowing De Bruyne to do the harder defensive bit shutting down Robertson, before Guardiola just gave up and took the German off. A terrible night for Gündoğan all round.

City were much more dominant in the second half, but it was an “agreed” form of control. Liverpool, happy with the three goals at home, just wanted to keep a clean sheet and thus retreated into a deep block. City did create a number of half-chances, but nothing too dangerous. I’m not sure there was really a way to avoid this happening, as at 3-0 it was always going to be attack vs defence, and Liverpool just defended well. It happens. The damage had been done in the first half.

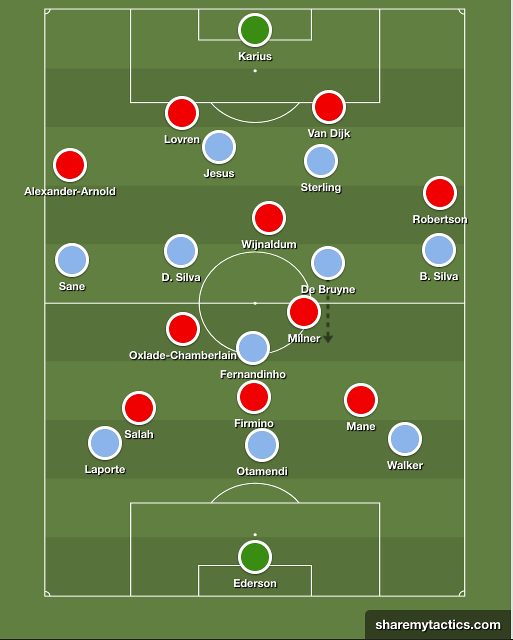

The time between these two legs is something I desperately wish had been chronicled in one of Martí Perarnau’s books. Guardiola’s main template for the second leg at the Etihad seems to be the 3-5-2 shape he used successfully in the early part of the season. That system featured three genuine central defenders with Walker and Mendy as wing backs. The midfield three of Fernandinho, De Bruyne and David Silva would function as normal, with Jesus and Agüero together forming an old fashioned strike partnership. It was really effective, but Mendy’s injury along with Sterling and Sané’s good form forced Guardiola’s hand, and he reverted to his usual back four shape.

Perhaps he felt, like his thought against Real Madrid in 2014 before he changed his mind, that three defenders would be the best way to defend against Liverpool’s counters. Perhaps he looked back at the 5-0 performance against Klopp’s side with the 3-5-2 and figured they needed that. Perhaps he just, as was claimed by many pundits, “went for it”. He reverted to the system, but there were issues. Mendy was a long term absentee, while Sterling and Sané were undroppable. Walker was his fastest defender, so his recovery pace would be needed in the back three. All of this meant that Bernardo Silva and Sané started as the wing backs, while Sterling joined Jesus upfront. It was certainly bold. Jordan Henderson’s suspension meant that Wijnaldum started for Liverpool in Klopp’s only change.

Did it work? Eh.

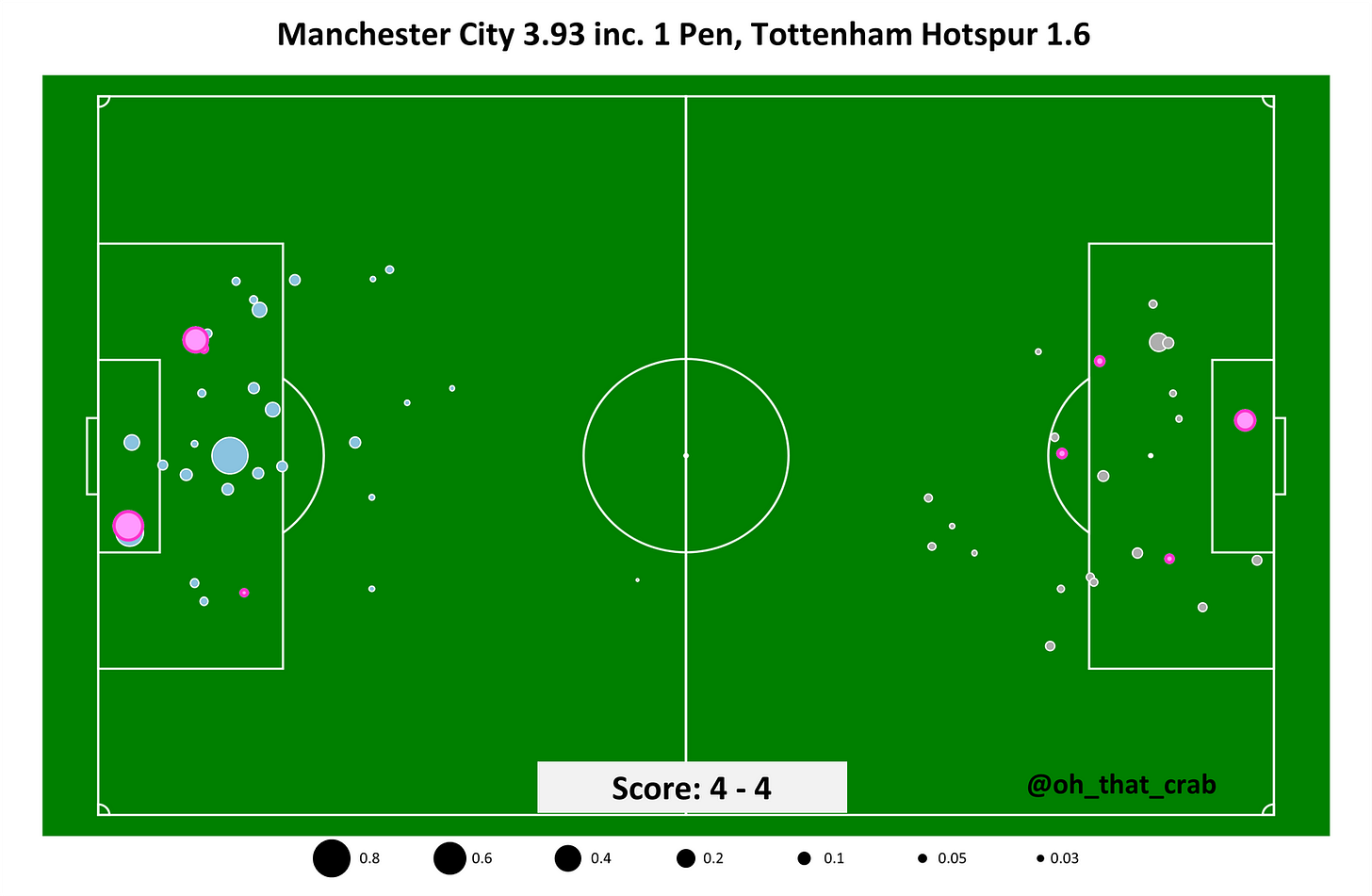

City clearly dominated the game at the Etihad. Liverpool were very fortunate to get two goals from their only two really good chances. That’s football for you. Liverpool only just edged the xG, 1.88 to 1.77, as seen on the graph below. But there’s a heavy dose of game state here. For three of the four halves in the tie, only one team was really interested in attacking. City were desperately chasing the game for the vast majority of this contest, and didn’t manage to create two expected goals. It’s certainly not as bad as the 5-1 aggregate scoreline would suggest, but it’s not great.

The first leg system caused all kinds of problems, and what we saw in the second leg just didn’t have enough of a spark to do what needed to be done. The obvious question is why they didn’t just play their usual set up, though Guardiola would surely argue that it failed in the league game at Anfield. But nonetheless, none of these changes did any of the things Guardiola wanted, and this is one that does have to go down as an error on his part. The plan was to prevent the counter-pressing and attacking transitions at the source, but it’s very hard to stop the best teams from executing at all on their plan A. There was no failsafe in case Liverpool broke through, and City paid the price.

No one knew it at the time, but the 2019 quarter final against Tottenham Hotspur should’ve been a banker for Man City. As recently as Boxing Day 2018, Spurs were one point ahead of City in the Premier League, but by the time this contest came around, the gap was 16 points in favour of Guardiola’s team. But even in that good late 2018 run, the expected goals were very sharply trending down. The quality of Tottenham’s starting eleven had deteriorated significantly, particularly in central midfield and at both full back spots. Mauricio Pochettino was finding all sorts of ways to paper over the cracks, but he could only do this for so long, and things were beginning to cave in. Not that many knew this at the time, of course. (Me. I knew. Not that I’m trying to brag.)

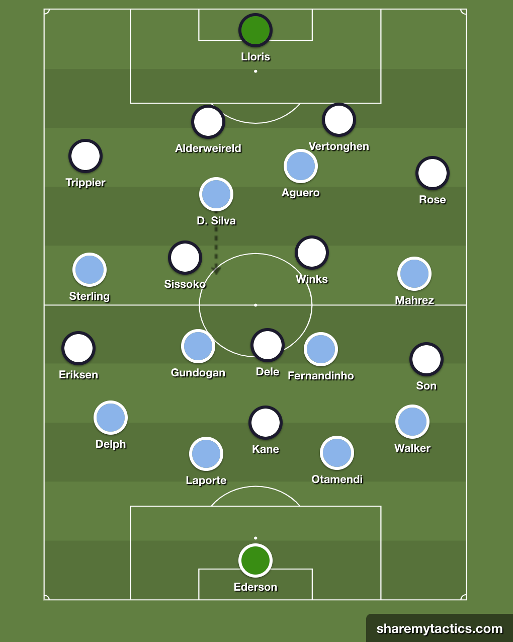

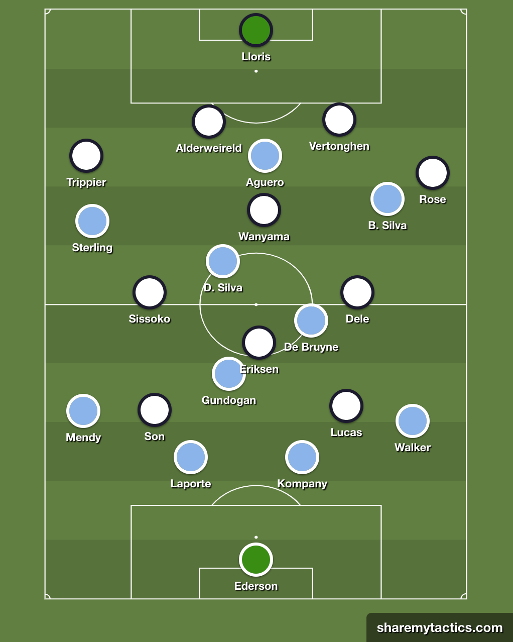

After flirting with some different shapes and styles, Spurs played the first leg at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium with the “classic” Pochettino system: 4-2-3-1 with pressing right the way to the opposing goalkeeper. The front four of Harry Kane, Dele Alli, Son Heung-min and Christian Eriksen are exactly the attackers we associate with that Tottenham side. The midfield double pivot, though, was an awful lot less assertive. Mousa Dembélé, a genuinely one off player in his ability to evade pressure, had hit the age curve and left for China. Eric Dier and Victor Wanyama had both hit poor form. Thus Pochettino used the partnership of Harry Winks and Moussa Sissoko. Both were pretty limited players, so City could flood that area like Guardiola likes to and dominate easily, right?

Of all the choices Guardiola has made in the Champions League knockout stages, the one he makes in the first leg here is the hardest for me to understand. City play an outright 4-4-2 without the ball, as David Silva pushes up all the way alongside Agüero. Sterling and Riyad Mahrez play wide roles on their “opposite” sides, while Fernandinho and Gündoğan form a straight double pivot. Silva drops deep in possession to make it much more of a 4-2-3-1, but without the ball it’s as “four four fucking two” as it gets.

I can only assume he wanted the side to stay more compact, and 4-4-2 remains the better shape to do that in. Maybe in Guardiola’s head, he was expecting the more dominant Tottenham of previous years, even if this feels out of character for such a meticulous coach. Spurs did attempt to play that high pressing, possession dominant game, but with such a flimsy midfield it could’ve been easily broken by just playing City’s normal system in that area. Move David Silva deeper and you’re always going to dominate with three good players against Winks and Sissoko. This seems so obvious to me that I can’t believe he didn’t do it.

Instead, he allowed Tottenham to have an element of control in the game but limited their chances. Guardiola’s tactical choice made it pretty drab to watch, and City never really created much outside of a very soft penalty early on. Agüero missed it, but you could hardly say City deserved to score a goal in this match. On the flip side, Guardiola’s plan “worked” and Spurs offered very little penetration, but for a moment of real quality from Son that took them ahead in the tie. Guardiola seemed to be very happy with his side’s performance, but based on everything since, I can’t help but feel he overestimated the challenge of Spurs. City playing the usual system are simply a much better side than c.2019 Tottenham.

Guardiola did, in all fairness, go for a much more conventional approach in the second leg at the Etihad. Gündoğan started at the base of the midfield three rather than Fernandinho (presumably an intent to control the game and dominate possession. Sterling started on the left, with Bernardo Silva playing from the right. Mendy played at left back to offer the overlap for Sterling’s more narrow positioning than Leroy Sané would offer. David Silva was still somewhat higher than usual to press Spurs’ centre backs. But overall it was a much more familiar City setup. Pochettino was without Kane, and went for his “Plan B” shape of a diamond midfield with two strikers.

The most obvious thing about this second leg is that the first 21 minutes were completely ridiculous. City scored from 3 of their first 4 shots, and Spurs 2 from their first 3. Neither side was able to begin exerting any control, but we ended that phase basically as we left it. Spurs were heading through (this time on away goals), but a single goal from City would turn the tie on its head. They had about 70 minutes to do it. Spurs caught some bad luck just before half-time, as Sissoko picked up an injury. With no midfielders on the bench, Pochettino opted to bring on a conventional target man in Fernando Llorente, prompting a change of shape and approach. Spurs, ahead on away goals, would sit deeper and play it long to the big man.

City really did dominate this period. They created a number of good chances Lloris was able to save. With Spurs essentially giving up contesting midfield, City’s control grew and grew. This was as well as Guardiola could hope for them to play. But then. Oh, but then.

Agüero gets the goal that takes City ahead, from a brilliant De Bruyne run straight through such a weak Tottenham midfield. Then, just over ten minutes later, a Tottenham corner leads to Llorente scoring off I think was his hip. Or it might have just nicked his arm on the way in. Regardless, a truly strange goal to score, especially at a point in the game when Spurs looked really on the ropes and hadn’t created much. Then it happens.

There are moments in football that are extremely funny to everyone, unless it happens to your team, in which case they’re obviously not funny at all and how dare anyone laugh. Believe me, I’ve been there. Anyway. After piling on so much pressure, City finally get the breakthrough with a Sterling winner in the 93rd minute. But then, in what still felt like a novelty back then, VAR disallows the goal for an offside in the buildup. City have blown it. Guardiola is going out again. Hilarity ensues.

But the reason this was so funny to many was because City were clearly the better side on the night, and overall dominant in the tie. Guardiola made to my eyes a clear tactical error in the first leg, opting for a cautious 4-4-2 instead of dominating in midfield, but it meant a tight game instead of a City blowout. The second leg saw him correct this error and easily outplay Tottenham. The only thing that saw Spurs through was Son’s outstanding individual performance. Otherwise, City were clearly the better side. I mean, just look at the xG map. It includes a dubious penalty missed, but still.

If you’re enjoying this, please read onto Part Four: The Fallen World for more.