Some rambling thoughts on finishing chances

Scoring goals is weird.

Manchester City were not short of chances in their 0-0 draw against Crystal Palace. It’s clear in the data but, most obviously, it would be clear to anyone who simply watched the highlights.

City took 18 shots worth 2.04 expected goals, at least according to Understat (yes, not usually my first choice, but FBRef doesn’t provide the values for each individual shot). If we put those values into Danny Page’s xG simulator, we see that, on average, we’d expect City to score at least one goal over 93% of the time. They were, it predicts, more likely to score four goals than the zero they actually managed, based on those chances.

This kind of game led to some very predictable cries:

“This is what happens without any top finishers”

“This is why they should have signed Harry Kane”

“City need Erling Haaland for games like this”.

Let’s be clear: if they can get him, Man City should absolutely sign Erling Haaland this summer. And if Harry Kane had arrived, I’m sure he would’ve added a lot to the team. But they’d be great additions because they’re great footballers. They’d be consistent outlets to receive the ball and make City even better at turning their dominance in the final third into chances. In most basic terms, they’d score lots of goals, and that tends to help football teams win matches.

But I don’t think they should sign these players to finish the chances they’re already creating.

Brighton and Hove Albion are a team that hear this a lot. They’ve scored fewer than expected in all three of Graham Potter’s seasons in charge. Clinical finishers, they are not. I don’t know who would be the Brighton equivalent of Haaland. Maybe someone like Danny Ings? Someone who can put the ball in the back of the net, unlike Neal Maupay.

But here’s the thing: Maupay is a touch ahead of his xG this season. Whatever problems Brighton have with finishing are collective, and wouldn’t be solved by someone else getting the striker’s chances. Maupay was on a terrible finishing streak last season but, just as the numbers would have predicted, he’s looking much more normal this campaign.

As for Man City, they’ve beaten xG in every one of the last five seasons. If the models tell us one thing, it’s that this team are very, very good at finishing chances.

There was an issue for Man City upfront against Palace. Their nominal striker Phil Foden only took two shots, and neither were great efforts. He only managed three touches in the Palace penalty area, fewer than centre back Aymeric Laporte (this time per FBRef, using StatsBomb data). Foden is obviously an excellent player and has shined in the false nine role over the last 18 months or so. But there are definitely the odd games where a more conventional striker would help them get the ball in the box quicker and give them another way of turning territorial dominance into chances. Haaland or Kane would’ve done all of these things better than Foden, but we’re still talking about a team that created enough to score.

City’s best chance fell to Bernardo Silva, who has been finishing his chances very well this season. Their next best opportunity was missed by Aymeric Laporte, but come on, no one picks their starting centre backs on finishing ability. City are “on course” for 89 goals this season, more than either of the last two league title winners. Yes, perhaps Liverpool are slightly better in attack than Guardiola’s team. But it’s not because City don’t have someone to finish those chances.

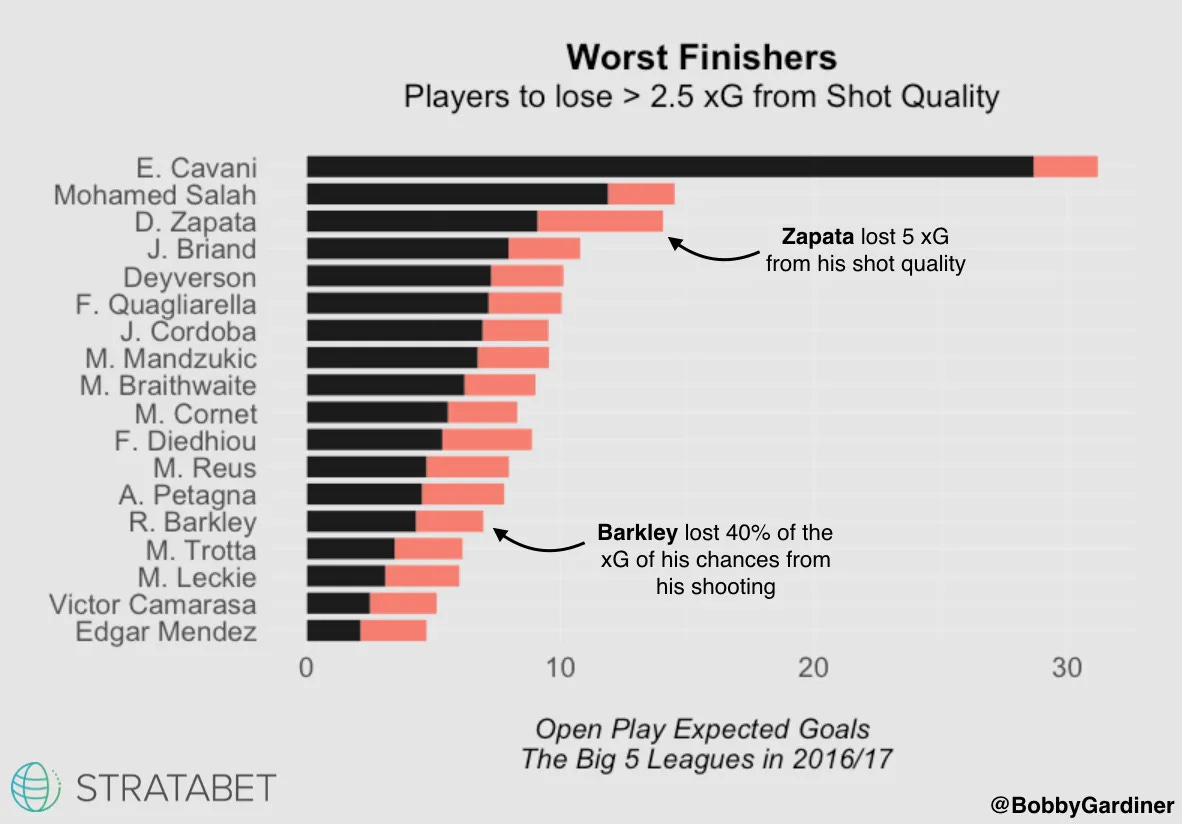

I do think this speaks to a broader disconnect around what “finishing” actually is. Analytics people have long been of the opinion that ball-striking ability is much less important than being able to get the chances in the first place. The best version of this argument I’ve read was from Bobby Gardiner, now an analyst at a top European club, for The Ringer. As he explains (using data that is unfortunately no longer available), the best finishers do add value to their chances, but this is dwarfed by the importance of getting the chances in the first place. But here’s the interesting thing. Below is a graph he produced on the worst finishers in the 2016/17 season. Look at the second name on the list.

I don’t know about you, but I think Mohamed Salah is a pretty good finisher these days.

(I suspect this perception he had of being a poor finisher at Roma is part of what led that club to cash in on him and keep then-31-year-old Edin Džeko. Nothing at all against Džeko, but I often wonder about the world where Roma sell him in 2017 and instead build around Salah.)

Every person I’ve ever heard who played professional football seems absolutely certain that finishing skill is a real and important thing. It would be incredible hubris to suggest this isn’t an important factor. But I question if we’re properly understanding what “finishing ability” is? What if, as we understand it, a good finisher is someone who first shows an ability to generate shots when receiving the ball in good areas, as well as simply striking the ball? I think xG has muddled our thinking on this a touch.

When I was growing up in the early 2000s, most football fans would’ve told you the best “natural finisher” in the Premier League was Ruud van Nistelrooy. He was probably the last old-fashioned poacher to thrive at the top of English football (though it’s arguably coming back in). While Thierry Henry was reinventing the striker position as one that could effortlessly link play and drift into wide areas before running in behind, his main golden boot rival was the exact opposite. You don’t have to watch a lot of this video to understand what sort of player he was.

Famously, Van Nistelrooy scored only one of his 150 goals for Manchester United from outside the box. Everything that happened outside of the opposition penalty area was the rest of the team’s job – he came alive within point-blank range. No one significantly overperforms xG from those kinds of situations. Van Nistelrooy, I suspect, was no exception (when I watched full games of his last year, he missed a fair few more chances than remembered).

But he was seen as an archetypal “good finisher”. This had nothing to do with his ability to strike the ball cleanly and everything to do with getting on the end of chances and turning deliveries into shots. That’s what a top finisher does. A lesser finisher, in the traditional sense we’ve used the term, wouldn’t quite get a toe on the end of those crosses, would hold onto the ball a little too long and allow the defender to get a foot in before pulling the trigger, would just not quite get ahead of the defender to bury that cross.

By that notion, Man City did a lot right against Palace. They turned their dominance into plenty of good chances, which is all I think you can realistically ask of a team. As for kicking the ball in the back of the net, well, that’s a strange force none of us fully understand.

Scoring goals is just really, really hard.

What I’ve read recently

Trying this new corner out, and we’ll see how it goes. Here are three articles I liked and thought were worth pointing out.

I really enjoyed Lewis Ambrose’s look at why Bayern have been stuttering recently, and whether it opens up a real title race in the Bundesliga:

Even before then the Bayern backline wasn’t as solid as the Julian Nagelsmann Leipzig side that had the league’s best defence last season, but they’ve been awful in recent weeks. The vertical, high-tempo, full throttle counter-pressing approach and shift to a move obvious three-man defence isn’t working, not without the Road Runner-like pace of Alphonso Davies at left-back.

Bayern are constantly open on the break and the midfield hasn’t adjusted to provide the backline with enough attention. When you take risks in the build-up to get as many players forward as possible, you can’t keep losing the ball in front of your defenders.

John Muller’s (behind The Athletic’s paywall, I’m afraid) look at Xavi’s tactical setup at Barcelona seems even more relevant in light of their demolition of Real Madrid:

The most surprising thing about Xavi’s new-style 4-3-3 is that he’s coaching his young midfielders to operate in very un-Xavi-like ways.

As a player, Xavi’s position was dictated by the ball, which seemed to get lonely if it left his feet for more than a few seconds at a time. When Barcelona built from the back, Xavi dropped deep to keep the ball company. When the ball arrived in the final third, so did Xavi. His job was to receive in small patches of grass and play team-mates into bigger ones. He didn’t create space — he discovered it.

Barça’s current crop of midfield wonderkids could play like him, or something close to it anyway, but they don’t. Instead of overloading the midfield like Guardiola’s Barcelona, Xavi’s team explodes outward in possession to fill as much of the pitch as possible. In this version of the 4-3-3, the two central midfielders operate like auxiliary forwards in an aggressive front five. They’re space creators as much as ball distributors.

In less tactics-y news, Simon Lloyd wrote about the sentimental value Man Utd would lose by rebuilding Old Trafford, even if the ground is in need of more than a lick of paint:

It's hard not to get a bit emotional about this sort of thing. A big part of being a football fan is embracing nostalgia, and nowhere quite stirs the soul of a supporter like a century-old stadium your dad - and maybe his dad before him - came to when they were kids.

It's for this reason that so many have found the news that United are giving serious thought to bulldozing Old Trafford to make way for a new one so hard to swallow. All those memories, all that history, torn down to make way for a glitzy state of the art stadium, fit for the modern era - whatever that is. It is, at least at this stage, just an option, but something that is perhaps not so far-fetched when considering who owns the club and the general sense of direction in which football appears to be shifting.

I really like the idea of a brief summary of a couple of interesting articles (or even tweets?) that you've found. Thought-provoking piece, as always!