The future of Amorim and United’s new style (guest post)

"The most that can be said about Amorim is that he has yet to lose 4-0"

Hi everyone, Grace here. Today I’ve got an excellent guest post for you from Catalina Bush, taking a look at Manchester United’s early returns under the new boss. I really enjoyed reading this and hope you do, too. Catalina is a Data Analytics Intern with Carolina Ascent FC and studies Sport Analytics at Syracuse University’s Falk College. Previously, her work has been published in The Transfer Flow, and she regularly shares U.S. football-focused data visualizations on Bluesky.

Data is from FBRef unless stated otherwise, and does not include the 2-2 draw against Liverpool.

It was just a few months ago that Erik Ten Hag—fresh off being wholeheartedly backed by his superiors—described his goal for Manchester United as “the best transition team in the world.” According to the former manager, it was an assessment based on player profiles, history, and ambition. Yet after he was shown the door and replaced by Ruben Amorim, the team looks farther away from that lofty goal than ever before. With no win in four Premier League games, despite a dramatic victory at the Eithad and a positive draw against Liverpool, questions are swirling (as they always do when it comes to United) about Amorim’s long-term vision for the squad. After all, his 3-4-2-1 system that saw great success at Sporting is a complete departure from United teams of the past, and all signs suggest that it will take time for the players to adapt. Will Amorim be afforded that time, or is he simply doomed to fail?

The Players

Personnel is certainly a sizeable consideration when switching a team to a three-at-the-back system. It’s a shape that requires some pretty specific roles you don’t always find in most squads. At Sporting CP, Amorim employed an eclectic mix of talent that was bound to be difficult to replicate at United — especially without a summer transfer window to get settled — and so he has been forced to adapt his system to the team while the team is adapting to him. Perhaps the largest hole in Amorim’s plan is the most obvious: where do the goals come from? Setting aside the four against Everton at the beginning of December, United have scored just seven in the other eight games. At Sporting, Amorim had a squad that scored; his challenge now is recreating that success at a team seemingly allergic to goals.

Part of the challenge in the attack over the last month has been who to play where. Bruno Fernandes picks himself, but the rest has remained in flux with Amorim clearly unsatisfied. Marcus Rashford has been sidelined due to off-field reasons and illness, leaving Amad, Alejandro Garnacho, Mason Mount (who quickly picked up an injury), Joshua Zirkzee, Rasmus Højlund and Antony. Of those players, Amad has impressed most and shown an ability to both create chances from the right half-space while also winning the ball back high up the field. Despite starting as an advanced wing-back against Everton, Amad has played most of his minutes under Amorim at the right-sided number ten spot. This leaves striker as the only position left up for grabs, where Højlund has started seven times in all competitions.

Beyond the front three, much has been made about United’s wingbacks and what types of players Amorim wants them to be. Many speculated that Amorim would try to deploy Garnacho, Antony or Amad in those positions, but despite a brief (and promising) foray into the latter, the coach has decided to stick with Noussair Mazraoui and Diogo Dalot instead. The decision to opt for fullbacks instead of wingers here can be seen as both a defensive and practical move. Firstly, Dalot and Mazroui can easily form a back five out of possession if necessary and don’t need to be told where to stand and when to tackle (though Mazroui’s reckless challenge on Justin Kluivert against Bournemouth may beg to differ). Additionally, with four healthy centre backs in the squad (meaning no need to play Mazraoui there) and only three fit wingers (meaning they’re needed up front), Amorim may have simply wanted to prioritise having options in the attack. While it makes sense from a squad-management perspective, neither Dalot nor Mazraoui are particularly prolific in the final third, creating a trade-off when it comes to the attack.

Amorim has two options here: start two players with a combined 0.02 xG per 90 minutes on the wings, redistributing attacking responsibility from five players to just three and putting more pressure on his forwards to produce, or play wingers at wing-back, reducing his options up front and likely weakening his defence in the process, with the theoretical upside of a more potent attack. Amorim chose the former, and to be honest, I don’t blame him; it makes the most sense. But it’s resulted in enormous pressure on the front three, none of whom are having particularly high-scoring seasons.

It also leads to a precarious balance among the players Amorim selects for any given matchday. A front three of Zirkzee, Amad and Fernandes lacks any box-crashing threat. Starting Garnacho at any of those positions means less creativity unless you move Fernandes back a line, which in turn reduces defensive stability in favour of a more direct attacker. Rashford up front lacks hold-up play and so on and so forth. While these are considerations any top-flight manager will need to make, let alone one coaching Manchester United, the players’ lack of familiarity with Amorim’s style and the pressure upon them to succeed offensively only exacerbates that need to get each teamsheet right. In United’s best attacking performance under Amorim, the 4-0 victory over Everton, we were given a glimpse at what a high-flying attack could look like: two goals via Amad’s savvy pressing, a deflected shot from Rashford, and another on the counter to seal the deal. While Arsenal proved too difficult to overcome, United had a chance against Forest to show the new coach just how special an Old Trafford comeback is. With Rashford on for Garnacho in the 59th minute and Amad still at wingback, Amorim once again had four dangerous attackers on the field at the same time. Just two minutes later, this glorious sight:

Four players on the charge, two dashing toward the center of the box and one delaying his run — a dream scenario. Although Amad played it poorly, Fernandes was able to convert… and was taken off just ten minutes later, halting the comeback in its tracks. What could have been is impossible to know, but it’s clear that Amorim’s offensive issues all stem from one core problem: it’s not that he has the wrong forwards on the field, it’s more that he doesn’t have enough. He can’t just plug and play, however; it’s worth noting that before the comeback, United had already conceded three times.

Amorim needs time to get his players healthy and ready to play — the returns of Rashford and Mount will eventually help — but he also needs time to teach his players and learn from them too: their weaknesses, tendencies, and abilities. In the meantime, expect him to stick with Dalot and Mazraoui, even if they don’t fully solve the defensive problems.

United’s tumultuous track record

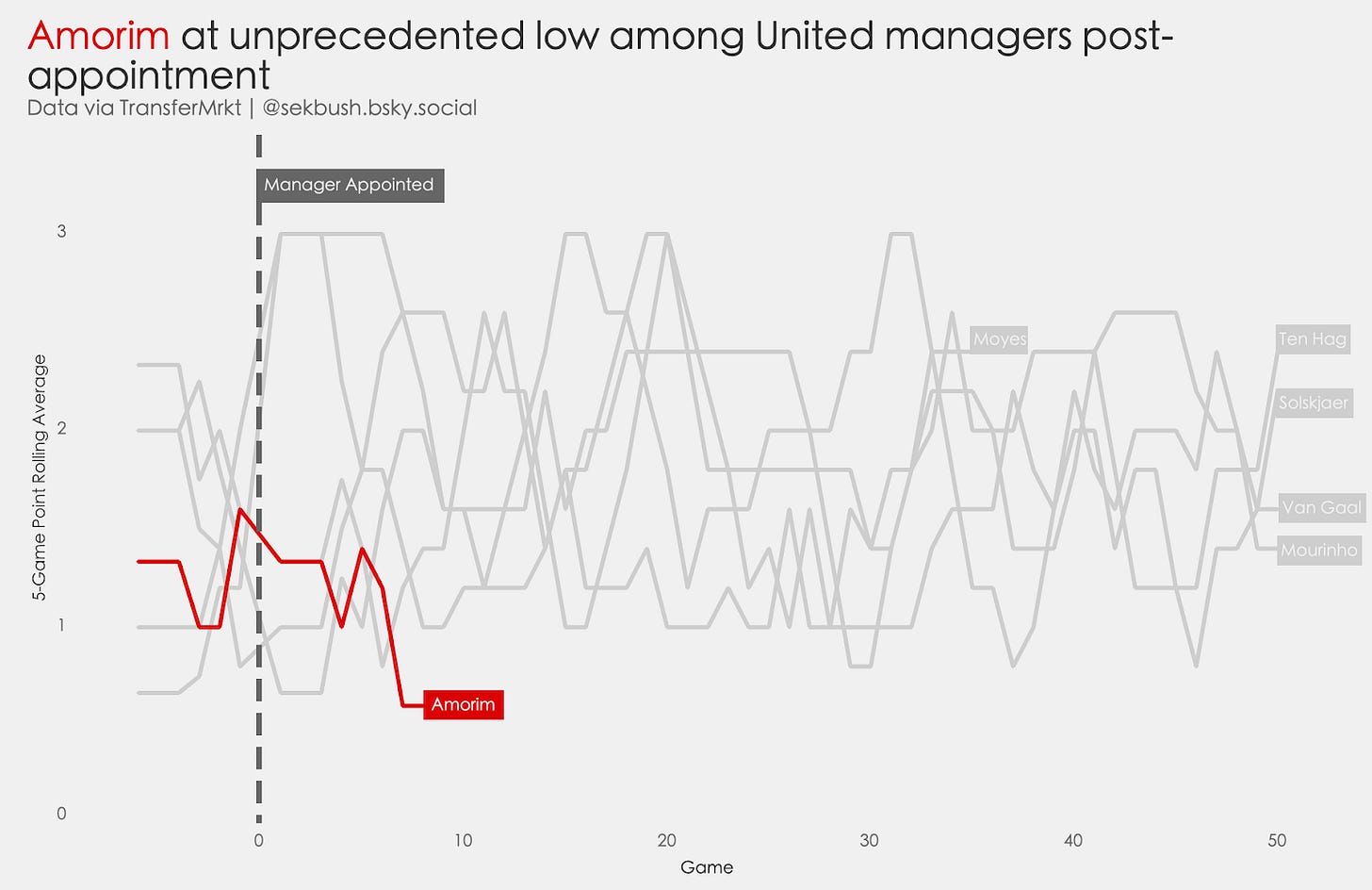

Firsts are almost always memorable: Ten Hag’s 4-0 disaster against Brentford, Louis Van Gaal’s 4-0 loss to MK Dons in his first league cup game and José Mourinho’s 4-0 defeat in his first game back at Stamford Bridge after joining United, to name a few. The most that can be said about Amorim is that he has yet to lose 4-0. But as far as openers go, a 1-1 draw against Ipswich is hardly impressive. And yet, despite a lack of truly shell-shocking losses — a mark of the times at United is how unsurprising it is to see them fall 3-0 to Bournemouth — Amorim is off to one of the worst starts a United manager has seen since Sir Alex Ferguson left in 2013.

It is not uncommon for a manager to do poorly in their first few games at Manchester United, but while the sample size is low, Amorim is off to the worst start in recent history. Post-Ferguson, every United manager has managed to reach ten points in their first eight games… except for Amorim. With the team sitting in 13th place and turmoil from the front office to the training pitch, one must ask: “Where does this United side go from here?” Presumably, up.

As much as this is a historic low for a team that has made historic lows a habit over the past few seasons, a potential upside of early failure is that expectations aren’t high, for fans as well as for the coach. Amorim has inherited a team unfit to play his style, in the middle of a season, with a leaky stadium and rats in the press room. His title as “head coach” rather than “manager” implies some limitations, but nevertheless, it is his job to right the ship. Perhaps it is more to his benefit than to his detriment that this season will most certainly be seen as a write-off.

Switching formations isn’t easy

The comfort for United fans is that Amorim is used to this. In his short time at Braga, he triumphed over Porto to win a league cup trophy, and did it again with Sporting just one year later. After joining mid-year the season prior and with just one summer to implement changes, Amorim successfully won Sporting their first title in 19 years, snapping a streak even longer than United’s. While the relative league difficulties remain far apart, it’s clear that at least in this regard, Amorim has some experience.

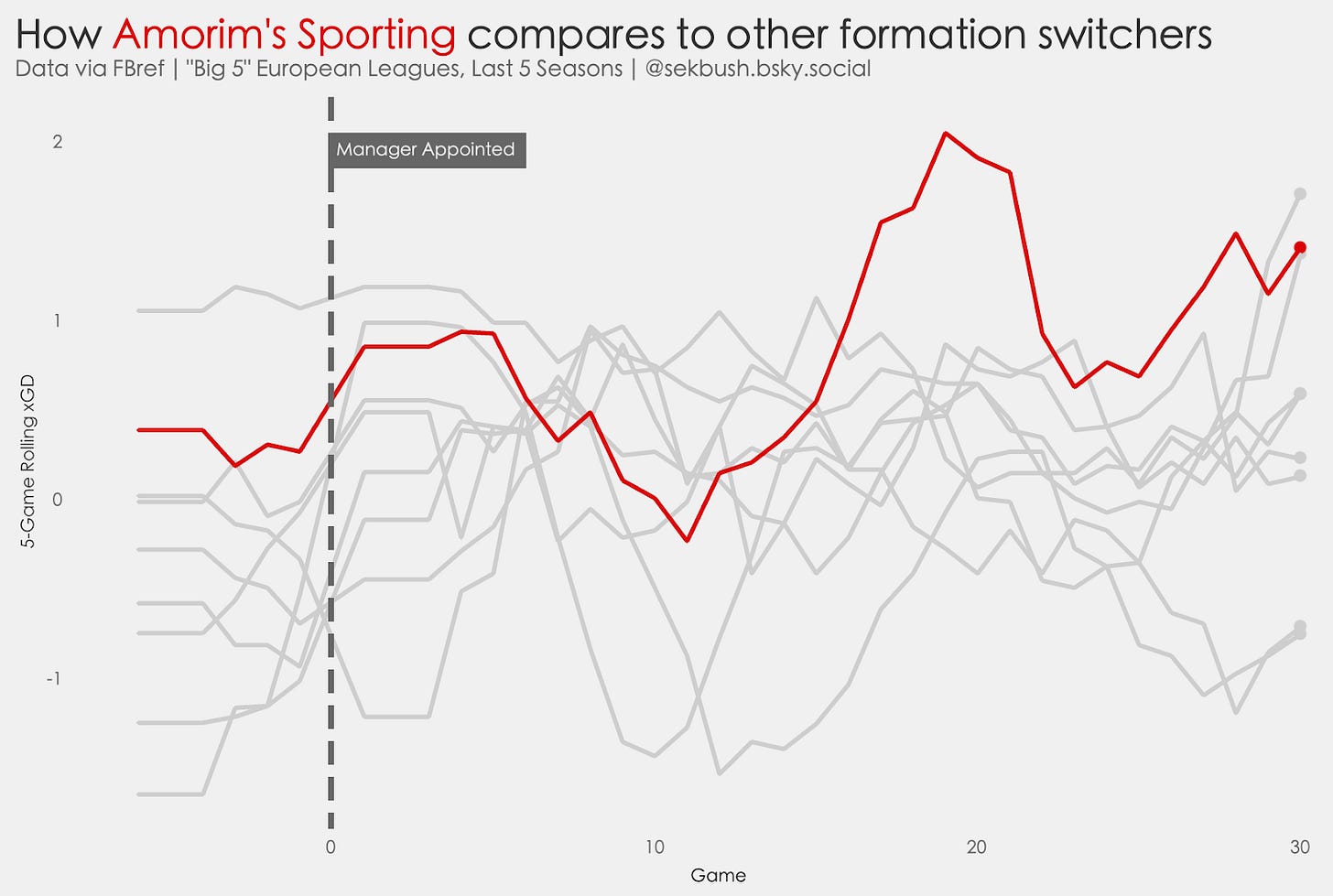

It’s also true that Amorim knows how to mold a team to fit his style of play. Changing to a 3-at-the-back system is not easy, yet few have done it better than Amorim himself with Sporting. In his first 30 games with the club, Amorim achieved a higher average xG difference than any team in the “big five” leagues playing a three-at-the-back system in the last five seasons — even higher than Xabi Alonso at Leverkusen. While there were lows and highs, Amorim is used to dealing with players who do not know how to play the way he wishes to play, and in the past, he’s done it very well.

In fact, changing the minds and intentions of his players will likely be the easy part. Convincing the fanbase on the other hand is a completely different, and much more arduous, undertaking. Ten Hag did it through grandiose statements: “Eras come to an end” and so on. Ole Gunnar Solskjær did it through “feel good” football. Mourinho did it by, well, being José Mourinho. Amorim must chart his own path; he has the time (for now), he knows what he’s doing, and he has some players behind his back. Now he must show his worth.