The Premier League is selling its UK broadcast rights again. What happens now?

Who will show the Premier League in the future, and have we reached a tipping point?

Let’s start by stating the obvious: the whole thing is a racket.

According to one website, the current cost of subscribing to all three services broadcasting Premier League games in the United Kingdom comes to £658.97 a year. That’s comfortably the highest price to watch the league of any country in the world. It’s 14% more than the second most expensive country, Norway (£579.30), 83% more than the United States (£360.85), 446% more expensive than the Netherlands (£120.74), 524% more expensive than Canada (£105.52) and 542% more than Australia (£102.60). All of those countries have a higher GDP per capita than the UK.

And all of those countries broadcast every single one of the 380 Premier League games played each season. That’s the standard to be expected in every country around the world except the UK and Ireland. That means on a per-match basis, here are the top five most expensive countries in the world to watch the Premier League on TV:

United Kingdom: £3.29 per game

Ireland: £2.44 per game

Norway: £1.52 per game

Denmark: £1.37 per game

Finland: £1.02 per game

After those five, no other country pays more than £1 per game (the US marginally escapes this at 95p). The UK is at over £3. The reasoning is pretty obvious: demand. The Premier League takes a radically different approach to packaging and broadcasting the games in the UK and Ireland compared to the rest of the world. In most countries, England’s top flight has to compete against myriad other leagues from both football and other sports. If they don’t put out a decent product at a reasonable price, people will switch over. At least that’s the theory of how competition in a free market is supposed to work.

Over here, the league can just assume its dominance. There is no conceivable world in which a rival football tournament would ever overtake the Premier League in popularity. Even the Champions League doesn’t drive revenues to the same extent. So instead of trying to compete on quality and price, the league seems to think the biggest risk is over-saturating the market. They keep the demand high by artificially limiting the supply. Not by playing fewer games, no. That would be ridiculous. They want to sell all 380 games abroad, and what’s expected to be 260 games in the UK for the next rights cycle.

I should say that the situation in Ireland is really deserving of its own article, but I’m not the person to write that. The British broadcasters largely share the same TV rights in Ireland, with I believe the addition of one Saturday 3 pm kick-off per week. I’ve said my bit on the blackout before, but simply abolishing it would probably give the UK an Ireland-like situation. The Premier League is by far the most popular football league over in Ireland, to the extent that it’s surely crippled the League of Ireland’s growth in an arguably colonialist manner. But I don’t have an expert understanding of the situation in Ireland, so this article is largely about the UK.

Crucially, and unlike the rest of the world, they split the rights up between broadcasters. It wasn’t always this way. Upstart Sky Sports won the league’s first ever TV deal from 1992/93 to 96/97 for what was then considered a huge sum of £304 million. Many thought Sky had overpaid, but it proved such a success that they more than doubled it next time, paying £670m to show the league for the 97/98 to 2000/01 seasons. Sky initially lost a chunk of games to rival NTL for the next round of rights, but that company’s financial troubles meant Rupert Murdoch’s empire again gobbled up the whole package, this time for £1.1 billion. Having seen off NTL, Sky was now truly the only game in town and, for the first time, the rights for 2004/05 to 2006/07 were actually slightly cheaper, at £1.024 billion.

The European Commission (remember when Britain was in the EU?) took issue with Sky’s dominance, deeming it anti-competitive and ruling that no single broadcaster can buy all the rights alone. This actually turns out to be wonderful news for the Premier League, as Setanta Sports buy 42 matches a season to Sky’s 96, and the 2007/08 to 2010/11 rights come in at a hefty £1.7 billion. Setanta were later replaced by ESPN and in turn BT Sport, but the model was now clear. The league didn’t ask for it, but generating a bidding war where multiple parties could buy pieces of the rights saw off the mid-2000s plateau and kept the line going up, crossing the £5 billion mark in the late 2010s. Though Sky were frustrated at first, they quickly found exclusivity wasn’t everything, and consumers were paying for multiple subscriptions at higher prices than ever. Everyone wins except the fans.

I don’t think regulators have quite understood the dynamic at play. Ofcom, Britain’s broadcasting regulator, has maintained a “no single buyer” rule, following the European Commission’s path. I think the regulators believe they’re creating competition in the market here, allowing consumers to choose between paying for Sky, BT (now TNT Sports) or Amazon. In reality, the same people are paying for all three, and the product was cheaper for the fans when Sky had a monopoly. I’m no economist, but this is a classic case of competition for the market, rather than competition in the market. Premier League broadcasters are not competing with each other in any meaningful way. True competition would be to end exclusivity, forcing the same matches to be shown on multiple broadcasters and making them compete on price and quality to earn our subscriptions. But I’m not holding my breath there.

There’s just one key problem for the league: what if the line isn’t going up anymore?

The last auction, for the 2019/20 to 21/22 seasons, produced a lower figure than the previous round. For Covid-related reasons, the league and broadcasters simply repeated this deal rather than hold another auction for the current seasons. The 2010s surge was driven by BT entering the ring and distorting the market like Roman Abramovich turning up at Chelsea. But BT and Sky were a well-established duopoly that tolerated each other rather than fighting to the death for more games. The league tried to shake this up by tempting tech companies into the ring and, while Amazon eventually bit, there was less interest from the sector than hoped, and the online retail giant actually got a reasonable deal.

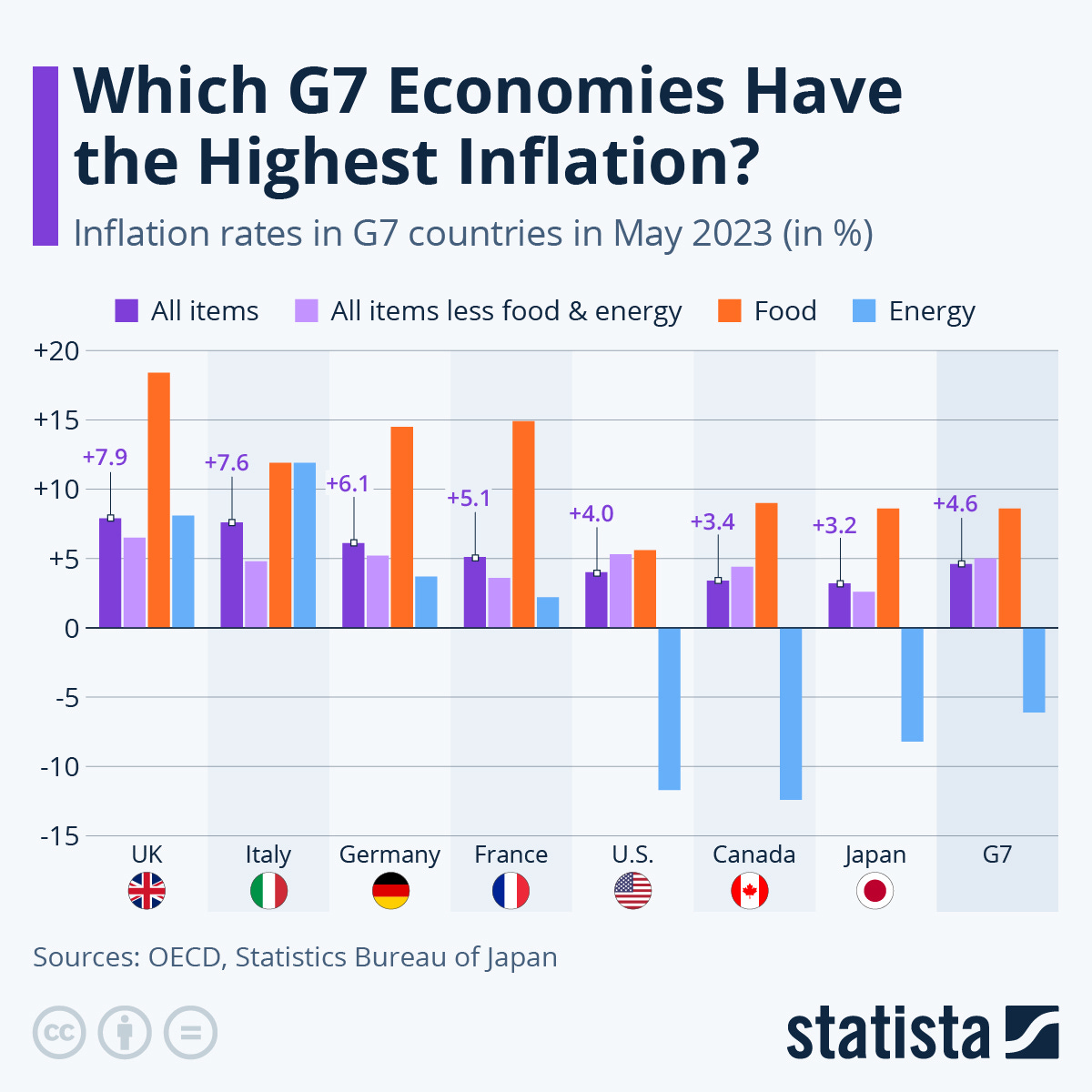

And that was in a much stronger economic climate. For reasons beyond the scope of a football newsletter, Britain has been particularly badly hit by the global economic winds recently, suffering the highest inflation rate in the G7. Meanwhile, at least one think tank puts the chances of a UK recession by the end of next year at 60%. All of this will of course trickle through to the broadcasters’ view on whether they’ll sell enough subscriptions to make a huge Premier League outlay viable.

The Premier League are probably hoping for more tech interest this time around to boost things. They’ll need it because the interest might not otherwise be as strong. Sky and the channel formerly known as BT are under different, more austere, ownership groups since the last auction in 2018. To counter these concerns, it looks like an extra 60 games will be made available, with the structure rejigged to potentially as few as four packages (rather than the current seven). Some creative thinking is certainly needed.

Many often float the idea of the Premier League going it alone and selling a direct-to-consumer streaming platform. I’ve personally never believed the numbers add up. Let’s imagine they sold a standalone product for £15 per month. Yes, that’s cheaper than subscriptions today, but they’d be offering nothing but the Premier League. To simply match the revenue generated by selling the rights today, they’d need about 10 million subscribers in the UK. Netflix, by comparison, has around 15.5 million subscribers in the country. Amazon Prime Video has 10 million, while Disney+ is on 7.5m. I just don’t see a world where the Premier League and literally nothing else to watch gets to 10m at a higher price than the standard tiers of all those services. The numbers don’t add up to me. The rights value is driven by companies using football to bundle with their other products, and stripping that away would lose money.

The Premier League’s auction for the 2025/26 to 27/28 seasons is expected by the end of this year. With all that in mind, let’s look at the state of each company that might be bidding for some of those UK rights.