The Sunderland Vortex

Why the fight to avoid relegation ensures that, one day, relegation will come for you.

When the breakaway clubs at the top of English football formed the Premier League in 1992, I don’t think they had any idea what they had just created.

Up until then, the pittance that English football made from television revenue was evenly distributed across the top four tiers of what used to be called simply “the Football League”. In modern-day terms, that would mean a struggling League Two side like Harrogate Town making the same money from TV broadcasting as Manchester City. Back in those days, live football wasn’t shown on British TV nearly as often as it is today, and all of it was free to air. The international TV market was an afterthought at best. Anyone with half a brain looking at it could see that the biggest clubs were leaving massive amounts of money on the table, so that’s exactly why they formed the breakaway Premier League, signing much bigger TV contracts and keeping that money in the top tier instead of seeing it trickle down.

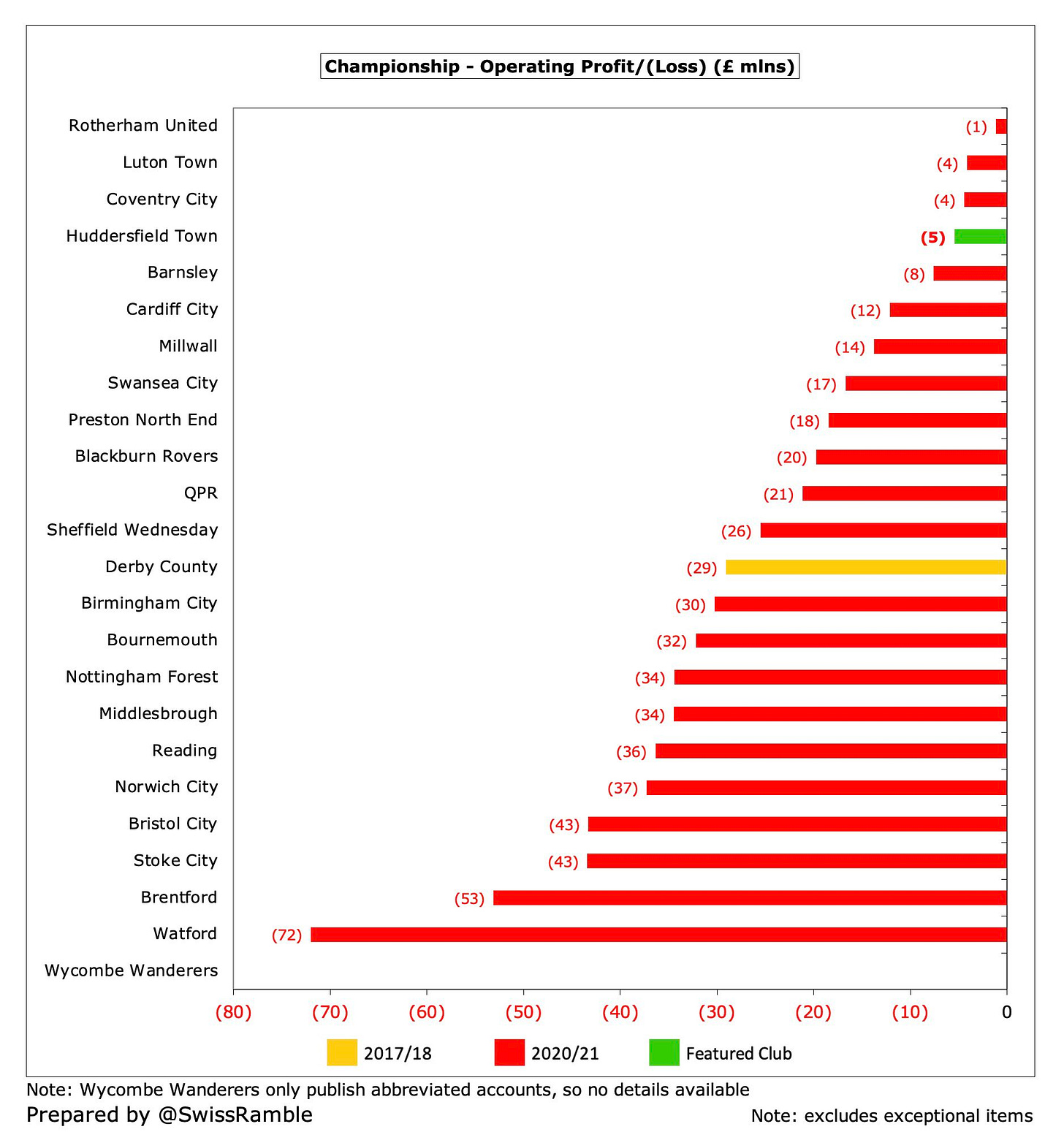

The old system meant that relegation wasn’t the end of the world. It mattered an awful lot on a purely sporting level, but the club’s finances were basically going to be fine if your team went down. The creation of the Premier League meant there was real money in English football for the first time. And with the rewards came the risks. The financial benefits of being in the top flight compared to what we now call the Championship became so great that clubs had to risk everything to be in the Premier League. On one side of the cliff edge, it meant that Championship club owners were willing to gamble huge sums of money in an attempt to get promoted. This could be disastrous for the clubs in the long run, but owners were willing to risk it all to play the lottery.

But this article isn’t about those teams. This article is about the teams that won the jackpot, living the dream of playing in the “best league in the world”. These clubs have huge locked-in revenues every year, thanks to the Premier League’s collective TV deal that might screw over everyone else, but serves all 20 sides very nicely. The Premier League is a brilliant cash cow for the owners of all 20 clubs. Until they get relegated, that is.

The term “Sunderland vortex” was coined by Mike Goodman and Michael Caley of the Double Pivot podcast. It gets its name, obviously, from Sunderland AFC and their… “eventful” decade in the 2010s. After a strong previous season, Steve Bruce’s Black Cats found themselves in a relegation fight in 2011/12. The board didn’t hesitate and sacked Bruce a month before Christmas, hiring Martin O’Neill in his place. O’Neill more than did his job, getting Sunderland to a solid 13th-placed finish, before it inevitably fell apart the following year. This time, Sunderland parachuted in Paolo Di Canio with seven games of the season remaining, and he just about did enough to keep the team up before, yep, things got rocky the next season and he was replaced by Gus Poyet. Inevitably, Poyet kept Sunderland up before getting into trouble the next year, when Dick Advocaat came in to save the club and should have left in the summer, but stuck it out until October before the Black Cats swapped him for Sam Allardyce. “Big Sam” stayed clear of relegation until the England job came calling (whoops), and Sunderland were forced to replace him with David Moyes. That year, the team completely fell apart and finished 20th.

Here’s the thing: every one of those managers wanted to reshape the squad. They all brought in their own players with short-term concerns to bring in a change. Over time, the rot got deeper and deeper as the club kept having to prioritise immediate relegation fights. It left Sunderland in a terrible situation when they did finally go down, suffering back-to-back relegations that landed the club in League One. Every manager wanted to bring in different profiles of player in order to win now, and what were Sunderland to do? They had to stay up. That meant kicking every long-term structural question down the road, where it would eventually bite them.

This is what the Sunderland Vortex does to teams. People like me always say that a football club needs a clear long-term plan, signing relatively young players to fit a clear tactical style that can be developed over years. When you’re fighting relegation every year, that becomes impossible. You might know that it’s a bad idea to give a four-year contract to a 30-year-old, for example. You know that it’ll cause you problems in the years to come, eating into your wage budget as he’s past the point of usefulness. But if he’s going to keep you up in the present, you have to sign him. The Sunderland Vortex forces you to make short-term decisions at the expense of long-term planning, because the cliff edge of relegation is just too great.

This ensures that, eventually, you will get relegated. Each successive “firefighter” manager has a harder job, with more dead wood in a more incoherent squad. And at some point, almost inevitably, you’re going to hire the right person. It might not be obvious at the time. Moyes looked like a perfectly sensible hire for Sunderland in the summer of 2016, but it went very wrong pretty quickly. Similarly, you’re going to be hit with a run of bad luck at some point. You might have a season where your best players get injured or your attackers just go on a terrible finishing run. It happens. When you’re having to play the odds on staying up every season, you’ll get a year where it doesn’t go your way at some point.

This doesn’t apply to every team in the Premier League. The “Rich Seven” – the traditional top six plus newly wealthy Newcastle – have enough money to spend their way out of any trouble like that. It’s a two-tiered league, and the rich clubs don’t have to worry about the ticking time bomb of relegation. A terrible season for the rich seven would be a midtable finish. A terrible season for the other 13 means getting relegated. That means those 13 clubs run at the constant risk of getting sucked into the Sunderland Vortex while the rich seven can plan ahead. But Sunderland are ancient history. Who, in 2023, is most at risk of getting sucked in?

We can immediately rule out Brighton and Brentford. Those clubs have clear identities and strategies to identify the right players. They seem to be doing everything right. That doesn’t mean things will keep going right forever. Southampton used to be the poster child for Doing Things Well, and look what happened there. But for now, neither club has to worry about the Sunderland Vortex.

Fulham are sitting very comfortably for now. I’m not sure they’re actually that good, and just about everything has broken for them this season. They’re punching way above their weight in terms of xG and, most fortunately, they’ve had an opposition player sent off five times this season (no other club has benefitted from this more than twice). But that’s fine because Fulham were not aiming for a top-six finish. This is a big overperformance, and it’s down to Marco Silva and the Khan family to turn it into something. But would you really be that surprised to see them fighting relegation next season?

Aston Villa seem on the right track with Unai Emery. I wouldn’t totally relax, but I think they seem pretty stable right now. Crystal Palace have stalled out this season after last year’s promise, but they still feel like there’s something of a plan with Patrick Vieira. I was really worried about the direction of the club two years ago, but they’re in a position to keep signing younger players to improve, even if they were to change the manager in the summer. Nottingham Forest haven’t been in the top flight long enough to really fall into any trap.

Then we get to the teams who really are in trouble. By xG, Leicester peaked in 2019/20 and have been getting worse every year since, to the point where they are deservedly in this bottom grouping. Barring an incredible turnaround, at some point, they will sack Brendan Rodgers. The next appointment will shape the future of the club. Get it right and they should be able to steer this clearly top-half talent back up the table. Equally, they might feel they need a firefighter, and could get trapped in a cycle of having to do stupid things to avoid relegation.

Wolves look like they’re in the Sunderland Vortex, but hope exists. Julen Lopetegui has started positively, with a sense that he can turn this strange mishmash of Jorge Mendes cast-offs into something. I don’t know if he will, but I know that if he doesn’t, things could go very wrong at Molineux.

Call me naive, but I still believe in Moyes’ West Ham. This is the same team and the fundamentals are good as everything has gone wrong in terms of results. The bookies continue to strongly back West Ham to stay up and I agree. That said, if he were to leave and West Ham stay up, they could absolutely enter the Sunderland Vortex almost instantly. I think they should stick to the plan.

Of the bottom four, I think Bournemouth aren’t quite there just because they haven’t been in the league for long. They’d like to be in the Sunderland Vortex. This is their first season back in the top flight and Gary O'Neil’s first as a manager. If they do stay up, let’s give them a chance to see if Bournemouth are building anything.

Then we get to the three teams who really are in the thick of it. Leeds have made Javi Gracia their third manager since returning to the Premier League. Gracia’s defensive solidity is totally different to Jesse Marsch’s counter-pressing style, which in turn was totally different to Marcelo Bielsa’s man-marking approach. Leeds used the transfer fees they received for Kalvin Phillips and Raphinha to overhaul the squad with Marsch-friendly players, some of whom may not fit what Gracia wants. The first job for Gracia is to stay up, which won’t be easy. If he pulls it off, he could demand a squad overhaul to suit what he wants, pushing Leeds into a cycle of short-termism. It’s not a great way to run a football club.

Everton could tell Leeds that. The best-case scenario for Sean Dyche is that he does something like Moyes in the 2000s, slowly building a combative team on a budget. I don’t think that’s particularly likely at Everton these days. Dyche is the firefighter to clean up the mess made by Frank Lampard, himself hired as a firefighter. Everton do not have a lot of money to spend, but what they do have will probably go on more short-term fixes, if they stay up. Everton were once a model for how to run a football club, and here they are circling the drain for the foreseeable future.

Southampton are probably going down, but they’re definitely in the vortex if not. I don’t think anyone really has a strong opinion on Rubén Sellés, but he’s clearly a fudge when they couldn’t find a manager they liked. They do have the second-youngest average age in the Premier League but, if they continue to fight relegation over the next few years, that could creep up as short-term thinking becomes endemic.

That’s what the Sunderland Vortex does to teams. It forces them to make bad decisions while eating up money. The unfortunate fact is that if you’re in the Premier League in 2023 without significant wealth, you’re on borrowed time. You’re playing musical chairs scrambling to avoid being one of the three clubs without a seat when the song stops. At some point, there won’t be three teams worse than you.

The fact that Palace found a way out of this vortex is still astonishing to me

I'd guess that the longer you're in the vortex, the harder it is to come back up? Is there any level of club wealth that would allow you to skip that, or even then do you think the drag of the unwanted firefighter players is too great?

I can't really think of examples, maybe Fulham and Watford who've broadly been able to spend their way back up, but they haven't had the multiple years of PL firefighting. Villa when they finally came up perhaps, as they would otherwise have been stuck long-term.