This is what Thiago brings to Liverpool

Spoiler alert: he’s good!

Thiago Alcântara’s first eighteen months at Bayern Munich were not easy. Injuries hit him hard, making an already difficult task of breaking into such a strong side so much harder. Most importantly, to just about everyone including the manager himself, he was the symbol of Pep Guardiola’s project to bring his Barcelona football to Bavaria. He was the La Masia golden boy taken by the man who most defined Barca since Johan Cruyff. Once seen as the heir to Xavi Hernández, he was now going to be the player to export that style of football to another country.

But Thiago himself didn’t see it like that. After one of the kind of cold December training sessions at Bayern’s Säbener Straße training complex that surely didn’t come too often at Barcelona, Thiago joined his new teammates for an intense run. This particularly un-Barca behaviour surprised many, including Barcelona, but the player was adamant this was what he wanted.

“I came here to be German, to toughen up and become more resilient”, Thiago explained*.

Thiago was born in Southern Italy, but I don’t imagine he calls it home. His parents, both established sportspeople in their own right (father Mazinho was a World Cup winning footballer, while mother Valéria played volleyball), whisked him back to their native Brazil, but by age five he found himself splitting his life between South America’s largest country and Spain of all places, thanks to his father’s career. After bouncing around various clubs in both countries, it was La Masia where he made something of a home at age 14. But it didn’t last. By age 22, both thanks to everyone’s beloved Barca board and his own desires, it was time to move on. After becoming “merely” Brazilian, Spanish and more Italian than Brad Pitt in Inglourious Basterds, it was time for Thiago to be German.

And so the cycle begins again.

Everyone loves making lazy comparisons based on a player’s nationality. Thomas Müller is efficient and ruthless. Harry Kane might not do many silky skills but he “knows where the back of the net is”. Neymar is full of trickery. Sometimes you can see it, but other times you get Sandro Tonali called the “next Andrea Pirlo” for little apparent reason. Thiago, to anyone who looks into it, defies national characterisation because he’s been to so many places. He’s the perfect third culture kid footballer: raised in different environments to his parents and more than happy to try somewhere new if he wants to reinvent himself a little. If modern football is defined by the breakdown of strict national identities for something much more universal and wider reaching, then Thiago fits right at home.

The thing about Jurgen Klopp’s Liverpool that should never be forgotten is that they weren’t always like this. They weren’t always so able to win games in any situation, regardless of what the opposition is doing. They’re the least flakey team in English football, but right before that, they were the most. The team you’d least trust to hold onto a 2-0 lead against a bottom half side. The team you’d know would do something stupid and shoot themselves in the foot. A team that played nice football but couldn’t figure out how to win for the life of them.

The issue, of course, was about personnel and tactics rather than mentality. Tactical switches to become much better in possession hit at the same time as significant signings to turn weaknesses into strengths. Out of nowhere, Liverpool became, as José Mourinho put it during his brief time at Sky Sports, a “complete puzzle”.

Mourinho has forgotten more than I will ever know about football, but I don’t think that’s quite true. Klopp solved the puzzle by conceding midfield ball progression and running things through the full backs. There are times win Liverpool look like they’re playing the 2-3-5 “pyramid” formation from over a century ago, as Trent Alexander-Arnold and Andy Robertson push up so high to form a front five across the width of the pitch. Those two are given a lot of free space by opponents who sit deep, so the response is to use them as aggressively as possible, encouraging them to take risks at every opportunity. Robertson is someone who makes dynamic runs and crosses, but it’s Alexander-Arnold who really feels revolutionary. As The Athletic’s Michael Cox put it, “Liverpool’s chief creator is their right back. And it’s difficult to think of another top-level club side — certainly in the modern era — who can say that”.

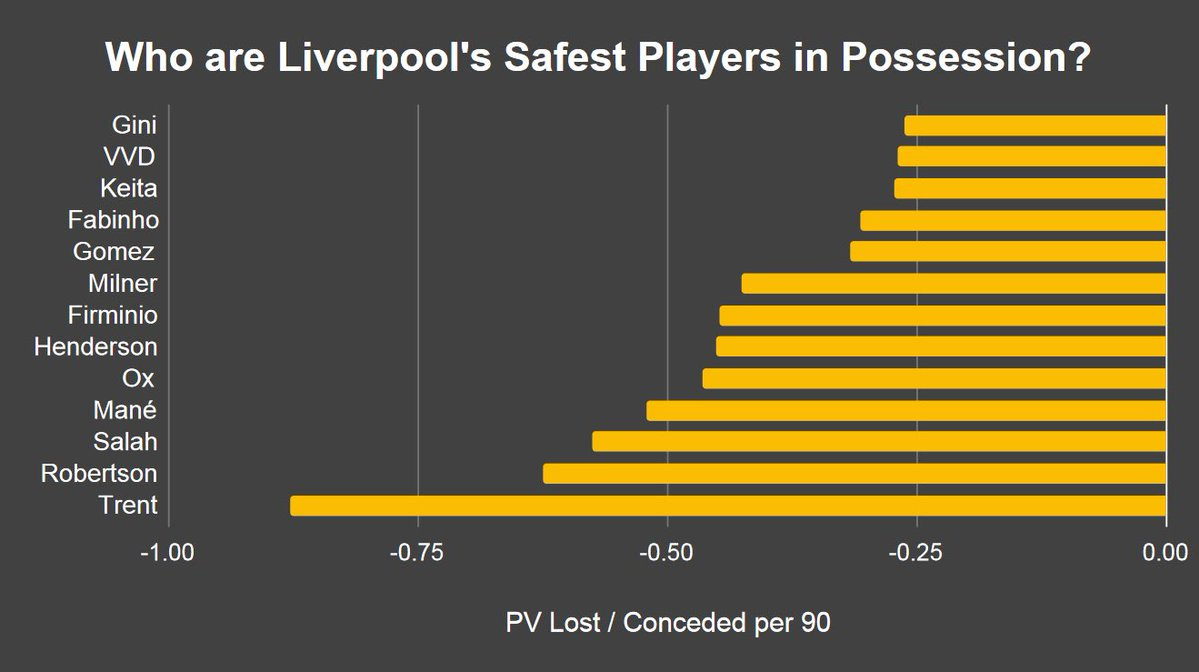

The flip side of this is that the central midfielders are really limited in what they’re allowed to do. There was a time when Liverpool fans criticised most of the club’s midfielders as “crabs”, since they could only move the ball sideways. When Jordan Henderson, Gini Wijnaldum and James Milner played together, the term “Brexit midfield” was trotted out (yes, Wijnaldum is Dutch, but that’s not the point). None of that technique and creativity, all running and aggression and hard Brexit football. It was entirely the point. Liverpool recognised that giving the ball away in the middle of the park was worse than losing it out wide, and so prioritised not losing it under any circumstances in central midfield. As Twitter user topimpacat showed in this graph, the possession value data shows that Wijnaldum in particular passes more conservatively than even Liverpool’s centre backs. Some of the great midfielders of the past twenty years have been praised for never giving the ball away. Klopp wants this, but without such a player, the instruction is slightly different: don’t do anything that might lead to giving the ball away.

“Every opponent makes the middle closed for us”, explained Klopp’s assistant Pepijn Lijnders. “So the space is on the sides. Openings must come from there”. Equally, Liverpool make the middle closed for everyone else as part of the deal, then “Trent and Robbo literally give us wings.

“But the rotten thing is: teams are already trying to stop that.

“It is up to us to remain unpredictable. We have used the corona time to good effect.

“There was time to work on new variants, bringing boys in a different role and in different spaces in training and seeing what the effect is.”

Rafa Benítez famously describes football as a “short blanket”. You can’t cover everything, so sacrifices have to be made along the way. The Liverpool team he built sacrificed creativity on the flanks in favour of hard workers, while the quality came from the “spine” with Steven Gerrard, Fernando Torres and Xabi Alonso. Klopp has done the exact opposite. But now that he needs to freshen it up to avoid growing predictable, how does he get more from the centre without sacrificing solidity? Does he curtail the full backs a bit? That doesn’t sound great. Does he make Liverpool much more open and exposed? I don’t think that’s likely.

But there’s always a very simple solution to any problem in football: buy a really, really good player in a position of need. Liverpool’s full back dominant system was built because they lacked such a complete midfielder to make things happen without costing solidity. Now they have perhaps the player in world football to do this. Thiago’s 10.5 progressive passes per 90 are far in advance of any Liverpool midfielder last season (per Football Reference using data from StatsBomb). His progressive distance gained from carries is ahead of all bar Naby Keïta. He does a fuckload of moving the ball forward. But he doesn’t give it away in exchange. No Bayern central midfielder completed his passes at a higher rate than Thiago’s 89.6% last season. None miscontrolled the ball fewer times than him and none were dribbled past less often. He was dispossessed about as often as Leon Goretzka (Joshua Kimmich comes out best here, but half his minutes were at right back, so it’s a tough comparison). He’s the best at moving the ball forward and he doesn’t lose it. He’s the cheat code. The missing piece. The guy who can give Liverpool creativity in the middle without losing any of the solidity.

Thiago as a human being is the antithesis of Brexit. As a footballer, he’s the opposite of the Brexit midfield. But he does all this without costing any of what made Liverpool such an effective unit in the last two years. His presence can cause so many more problems for opponents, potentially opening up even more space for the full backs in the process. He solves problems for Liverpool by creating them for everyone else. Thiago has it all.

*From the book Pep Confidential by Martí Perarnau, chapter 38 page 370