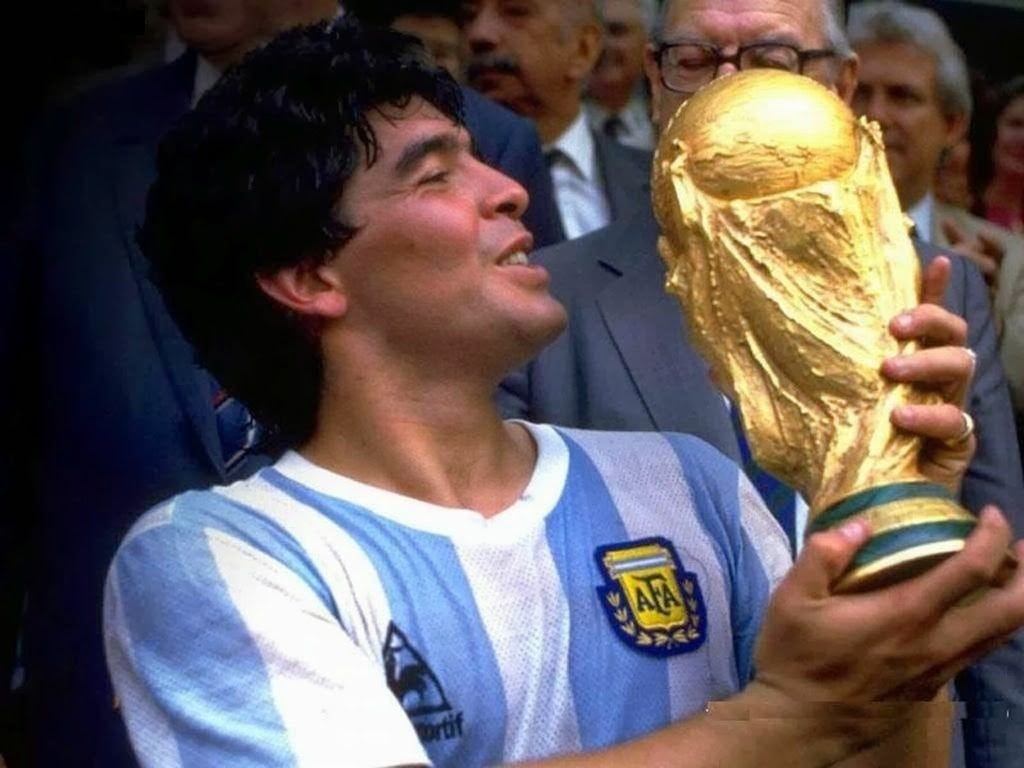

Unlocked: How good was Diego Maradona REALLY at the 1986 World Cup?

The GOAT of GOATs, revisited.

Hi everyone, I’m away this week, so I’m re-running this old edition, previously for subscribers only but this time available to everyone.

There are two ways of looking at Diego Armando Maradona.

On one hand, he is the greatest there ever was. Obviously. It shouldn’t even be a question. Back when the World Cup meant everything, he dragged Argentina to the title almost single-handedly. He embodied an entire nation in a way no other footballer ever could. More so than any other country on the planet, when you think of Argentina, you think of football. And when you think of Argentine football, you think of Maradona.

He left Barcelona to join minnows Napoli and took them to the Serie A summit, too. This wasn’t someone who had the privilege of being surrounded by world class players, as the modern elite do. This was someone who did everything off his own back, a god who pulled mortals up to his level. In the old days of muddy pitches, violent challenges and alcoholic players, Maradona played like it was 2020. The man has the aura about him. On a narrative level, no one will ever come close to him.

On the other hand, he was scoring about 10-15 goals a year in Italy. For a player of his reputation, you’d think he’d do a bit more in the numbers. His peak was pretty short lived and erratic. All he has to show for it is one European league title, a UEFA Cup medal, and that World Cup. How can you even compare him to Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo? It’s a blatant nostalgia bias, surely.

We do have to adjust our lenses for 1980s football. This was a time when European leagues only allowed three foreign players in a side, when TV money and commercial revenues had not yet consolidated the wealth for a handful of elite clubs. It’s become very fashionable to besmirch the World Cup these days, to claim that the Champions League and Europe’s top five leagues are the real pinnacle. But this was back when no club could boast the concentration of top players that a whole country had.

"Football should always be played at the highest possible level", the great former AC Milan and Italy manager Arrigo Sacchi claimed in the old days, "and no club will ever reach the level as an international side”.

Outside of Italy, most everyone would say Maradona’s most iconic achievement was winning the 1986 World Cup. That goal VAR would deny in a heartbeat these days.And then that goal no one could ever question. It was the pinnacle of football in the twentieth century.

But how did it actually go? Was he actually all that? Are everyone’s hazy memories clouding serious judgment?

Thanks to the miracle of Footballia, we can take a closer look.

2nd June 1986. Game number one. South Korea. Estadio Olímpico Universitario in Mexico City. The footage is an awfully grainy transfer of what looks like a VHS recording, so it’s hard to make out the individual players. It doesn’t matter, because you just know when Maradona has the ball for three reasons.

The first is that the cameras always cut to a close up when he has it. This is before he’s even done anything at the tournament, and he’s already far and away the star attraction. Everyone watching this game is waiting to see what he does.

And that includes South Korea. Contrary to just about every racist stereotype, the South Korea players are going in hard on Maradona every time he has the ball. All anyone wants to do is foul him. But in some ways he seems to like that. Most obviously, he’s a dead ball specialist, so any attempt to work his magic there isn’t the worst outcome. But more importantly, his deceptively good body strength and low centre of gravity makes it easier for him than most to wriggle out of those challenges. And then, being that he’s Maradona, he’s sucked so many players towards him, so there’s suddenly plenty of space for others.

And then finally, you always know he’s on the ball because he’s so good. You know when Messi has those games where he might not have done something obviously amazing, but yet every touch he takes is just so much crisper than anyone else on the pitch could dream of? Maradona had that quality.

Maradona doesn’t score in this game, but he’s the key driver of all three goals. The first two come from his dead ball quality, and the third from a dribble and low cross into the area. This about sums up the game for him, in which Argentina relied so much on his delivery with speculative balls, but he’d occasionally add in a dribble. He was like if Kevin De Bruyne also happened to be able to just slink past people at will. If we had the data, any kind of statistical model looking at expected possession value, progressive passes and runs, entries into the box or final third and all that good stuff would’ve surely loved Maradona in this game, even if he didn’t really try to involve himself in goalscoring. Carlos Bilardo’s Argentina famously were not doing a lot of attacking. Think Mikel Arteta’s Arsenal: getting into a deep block without the ball, then passing it slowly for extended periods with it. As it was 1986 and pressing was not in fashion the way it is today, this meant they could kill games pretty easily. When they needed to attack, they could just give it to Diego.

All of three days later, Argentina were playing again, this time about 90 miles east in Puebla. Opponents Italy had five days’ rest, which feels like it would be a scandal today but back then didn’t get much of a mention. There have been better Italy sides than Enzo Bearzot’s 1986 vintage, but watching the game back today it’s clear that they were a serious team. This was a really good closely fought game. While South Korea didn’t have a plan for Maradona beyond “foul him”, it’ll surprise no one to learn that Italy were much more defensively sophisticated. Napoli teammate Salvatore Bagni gets the daunting task of man marking Maradona, but there’s a collective effort to get tight to him. He gets very few opportunities to float those beautiful balls in over the top the way he did last time.

But we’re talking about Maradona at the 1986 World Cup here, and if he wants it, you can’t really stop him. This felt much more like a classically “Maradona performance”. With the Italy defenders getting so tight to him, it’s his close control that really comes to dominate. He drops deep less frequently and really wants to either dribble or play tight through balls. If the first game saw him create chances like De Bruyne, then this was more like David Silva.

Oh, and he scored this goal, which was pretty good.

Maradona also proved an impressively admirable defensive contributor in this game. It wasn’t the most structured of defensive roles, and he seemed happy to just run around and chase the ball at times when Italy were in possession. But he was definitely a beneficiary without the ball, making some surprisingly crunching challenges and looking the part. It should probably dispel any doubts, just in case you had any, about Maradona playing in a modern pressing system.

If those were the two Maradonas, then we saw a little of both against Bulgaria back at the Olímpico Universitario five days later. We also saw a much more complete attacking performance from Argentina. Jorge Valdano and Jorge Burruchaga proved fine supporting players for the main man, and this was a much more varied attack for it. Maradona’s “gravity” was a huge factor in this. It’s something a lot of great players have, so it’s no shock to see it here. Defenders just always need to be occupying him, and thus through his presence he’s creating space for Valdano and Burruchaga. This isn’t to say he didn’t create value. He was pulling the strings as a playmaker, and his delightful cross for Burruchaga’s goal was one of a number of good chances he provided. But he was a facilitator for much of this one, and allowed others to flourish. A lesser performance by his standards, but superb stuff nonetheless.

No international fixture has been played more times than Argentina against Uruguay. It might not be quite Brazil or a certain country coming up soon, but we’re still talking a serious rivalry. And yet the 16th June 1986 in Puebla was the first time Maradona had faced his Southern Cone neighbours at senior level. The most iconic player from either country was finally getting a chance to leave a mark on this fixture.

It was in truth something of a strange game for Maradona. Uruguay constricted his space quite well in the areas he wanted to operate, so he often drifted wide and looked to cross the ball in or beat a man to cut into a dangerous area. It was obviously effective because he’s Maradona, but Uruguay did an admirable job of stifling him.

It was a game where others’ poor finishing denied him some spectacular assists. This appears to be a theme with Maradona. Sometimes, if you want something done right, you have to do it yourself. But what’s been surprising is how little he does it himself. Maradona is not a guy who gets a lot of high-xG chances. He seems very happy to look to play it to teammates, often because he’s drifted wide, rather than coming inside and taking on the shot himself. It might be the biggest difference between what a number ten was asked to do in his day compared to Messi’s. In the modern game, Maradona would be pushed towards being a true goalscorer, getting into better areas and taking on the responsibility himself. Back in 1986, though, he was very much free to drift around outside the box and not really bother trying to get on the end of something. The chances he does get are generally ones he created himself. He’s no one’s idea of a poacher.

Ok, let’s get to it. 22nd June. England. Estadio Azteca. You know the story.

Sir Bobby Robson was a superb football manager deserving of all his plaudits, but he was not one of the great tactical thinkers. To call England’s attempts at stopping Maradona “primitive” would be a hell of an understatement. You can imagine Robson, his assistant Don Howe, and captain Peter Shilton all saying the same thing:

“Rough him up. Go on, lads. Rough him up”.

So. Many. Dangerous. Challenges. If I didn’t know that he was going to score the greatest goal in the history of football, I’d guess on more than one occasion that he’d received a concussion. In the modern game, we’d be talking about an England side down to maybe six or seven men. Whenever he had the ball, white shirts would swarm him and everyone would want to “leave one on him”. Maradona really approaches it by just dribbling at England much more often than he might otherwise. England generally sit very deep, but swarm Maradona, which leaves a very poor defensive structure for him to exploit when he can. He’d obviously thought about it beforehand and decided this was a contest for dribbling rather than exquisite passes. He was right.

I know there are people out there who don’t see the Hand of God as anything other than cheating and I respect that. It’s a view of football I understand, but it’s not one I hold. Considering the level of violence dished out to Maradona, I’d say he was a victim in this contest much more than a perpetrator. And the goal is an incredible moment of improvisation. Minutes earlier, Terry Fenwick raises his fist in the air while competing for a ball around the halfway line. Maradona just seems to almost exactly copy this bit of foul play, but to score a goal. He thinks quicker than everyone else on the pitch and gets his reward.

The second goal, well, you’ve seen it. But this was what Maradona had been working towards the whole game. Six years earlier he came close to scoring a similar, but less spectacular, goal against England. This time, he wanted to do it right. He knew how easily he could turn the English players inside out with his dribbling, and he went for it every time. When it worked, it really worked.

Astonishingly, we actually have data on this game. Opta seem to have collected it at some point and WhoScored put it online. What we can see is a few things. First of all, how Maradona completely took the game away from England. When it was still a contest, Robson played things very conservatively, with his side only taking four shots but keeping Argentina to speculative efforts. Then Maradona delivered and scored two golden chances, and that was the game. England finally started attacking, but it was far too late. The damage was done.

The second thing in the numbers is my god what a game he had. Argentina take 15 shots on the day. Seven of those are from Maradona, and another five are chances he created. Twelve successful dribbles. The man was on fire however you look at it. If this is the “official” greatest ever performance by a player in a single game, it certainly has the numbers to back it up.

My word he was good that day.

If you want to read more on the numbers behind this game, I’d recommend checking out what Nick Dorrington wrote at StatsBomb.

In some ways, the performance against Belgium in the semi-final was his most composed. He still goes for some spectacular dribbles, but not quite as often as he did against England, perhaps feeling less pressure in a game far from a heated rivalry. He runs the game, making better but less obvious decisions, creating danger but without rushing it too much. This was a refined Maradona.

And then he just kind of decides to win the game in the second half. He comes out taking a lot more shots on himself. As usual, none of them are really created for him by others, as he prefers to generate chances himself, which he either takes or lays on to someone else. The first goal is a delightfully cheeky chip across the face of goal. The second is an incredible dribble straight through the Belgian midfield of the sort you associate with him. It’d be the goal everyone remembers if not for the England game. Maradona was prodding throughout the first half, but then he just, for the second match running, completely takes the game away in a short space of time to send Argentina through.

The final against West Germany is not widely regarded as his game. He didn’t score any of the goals, though he did provide a wonderful assist for Burruchaga’s winner. But even in a game like that, it’s still just obvious he’s the most talented player on the pitch. He dribbles past so many opponents and creates some really good chances, but things just didn’t quite break his way. It didn’t matter in the end, but it should be noted that even when Maradona wasn’t extremely on, he would still be Argentina’s most impressive player.

You can’t understand the player without appreciating the tactical environment he was in. This was a true number ten being given the freedom to make his own decisions on the pitch and run the show. Like Messi, he’d often stand around the pitch waiting for something to happen, but appreciating exactly what he needed to do to influence things. Unlike Messi, he wasn’t regularly breaking goalscoring records.

But I think that was a reflection on role and era more than Maradona as a footballer. His main assets were combining an astonishing passing range with close control and an unusually stocky body type that meant he could dribble past anyone for fun. In the modern game, he’d probably be turned into a ruthless goalscorer, getting into dangerous positions over and over again. But in the 1980s, his game was much more about receiving the ball outside the box and either driving forward or putting a perfectly weighted ball in.

Football is always changing, and Maradona would be something different today. But it’s extremely clear watching the footage what a phenomenal talent he was. There should be no question of just how much he elevated that Argentina side. This was someone taking football to the limit. That it took decades for anyone else to catch up tells you everything you need to know: Diego Maradona was unprecedented in football. The guy was just something else.