What's Boehly's plan at Chelsea?

He's not shy. Where's this going to go?

Todd Boehly isn’t afraid of the limelight.

That’s what sets him apart from most American owners of Premier League clubs. John Henry, the Glazers, the Kroenkes and even other people involved in Chelsea’s ownership group hate being seen. They want to go about their work as privately as possible, skirting the press at every opportunity. Not Boehly, though. Boehly loves the attention.

Outside of Chelsea and the Los Angeles Dodgers, Boehly has significant financial interests in arguably the only industry in the world to receive more media coverage and spotlight than elite sport: Hollywood. His holding company, Eldridge Industries, owns a significant stake in MRC, the studio behind films like Knives Out and TV series like Ozark. He’s a significant backer of A24, the indie studio beloved by Film Twitter and Letterboxd users responsible for critical darlings like Everything Everywhere All at Once, Moonlight and Uncut Gems. Through a labyrinthine business collaboration with rich kid hotshot Jay Penske, he’s been involved in virtually monopolising the Hollywood trade press, bringing eternal rivals Variety, The Hollywood Reporter and Deadline under one roof.

His showiest move yet came in the last few months. The Golden Globe Awards, an eternal precursor award to the Oscars that gets mostly watched to see A-list celebrities get drunk with each other, nearly went extinct the previous year (for the unfamiliar, it’s best summed up as “not the Oscars, the other one”). The organisers of the awards were beset by scandals around corruption and racism, leading to a widespread boycott that saw TV broadcasters refuse to air the ceremony and Tom Cruise return his previously won awards. It looked like the Globes were deader than dead, until Boehly saw a value play.

Through some convoluted means, Boehly took control of the organisation behind the Globes, the Hollywood Foreign Press Association, and turned it into a for-profit company. His company Eldridge already owned the producers of the televised broadcast of the Globes, Dick Clark Productions, so this really was a complete takeover by Boehly. He made sweeping reforms behind the scenes, promising to clean up the organisation and move past the scandals. I sometimes wonder how much of Boehly’s business strategy is about the famous people he wants to hang out with and the parties he wants to attend.

But he has big plans with the Globes. “My No. 1 goal is to grow the brand”, Boehly told the Los Angeles Times. He wants to do this through “events around the world under the Golden Globes brand”, making the whole thing bigger than ever. This could reinvent the wheel of awards shows, making a year-round splash all built around the name value of the Golden Globes. Boehly’s never shy of splashy ideas and chances to dazzle us with far-off visions.

There’s just one tiny problem: the Globes’ US broadcast partner, NBC, is widely expected to cut ties. Airing the awards on American television is by far the Globes’ biggest revenue stream, and the whole thing looks like a lot of nothing without it. And that’s really where we’re at: Boehly’s making some bizarre contract structures and radical promises of a big and bold future no one can envision. At the same time, everything looks like it’s up in flames in the present and he doesn’t seem to be holding a fire extinguisher.

About eight months, 18 players and £666 million in transfer fees ago, Boehly and Clearlake Capital bought Chelsea Football Club. Boehly himself is rumoured to own about 20% of the club, but he’s certainly been the most hands-on member of the consortium, naming himself the chairman and, until recently, interim sporting director. He’s been the one making deals, hiring and firing managers, and overseeing the drastic reshaping of the club. This is his Chelsea, even if he only owns a fifth of it.

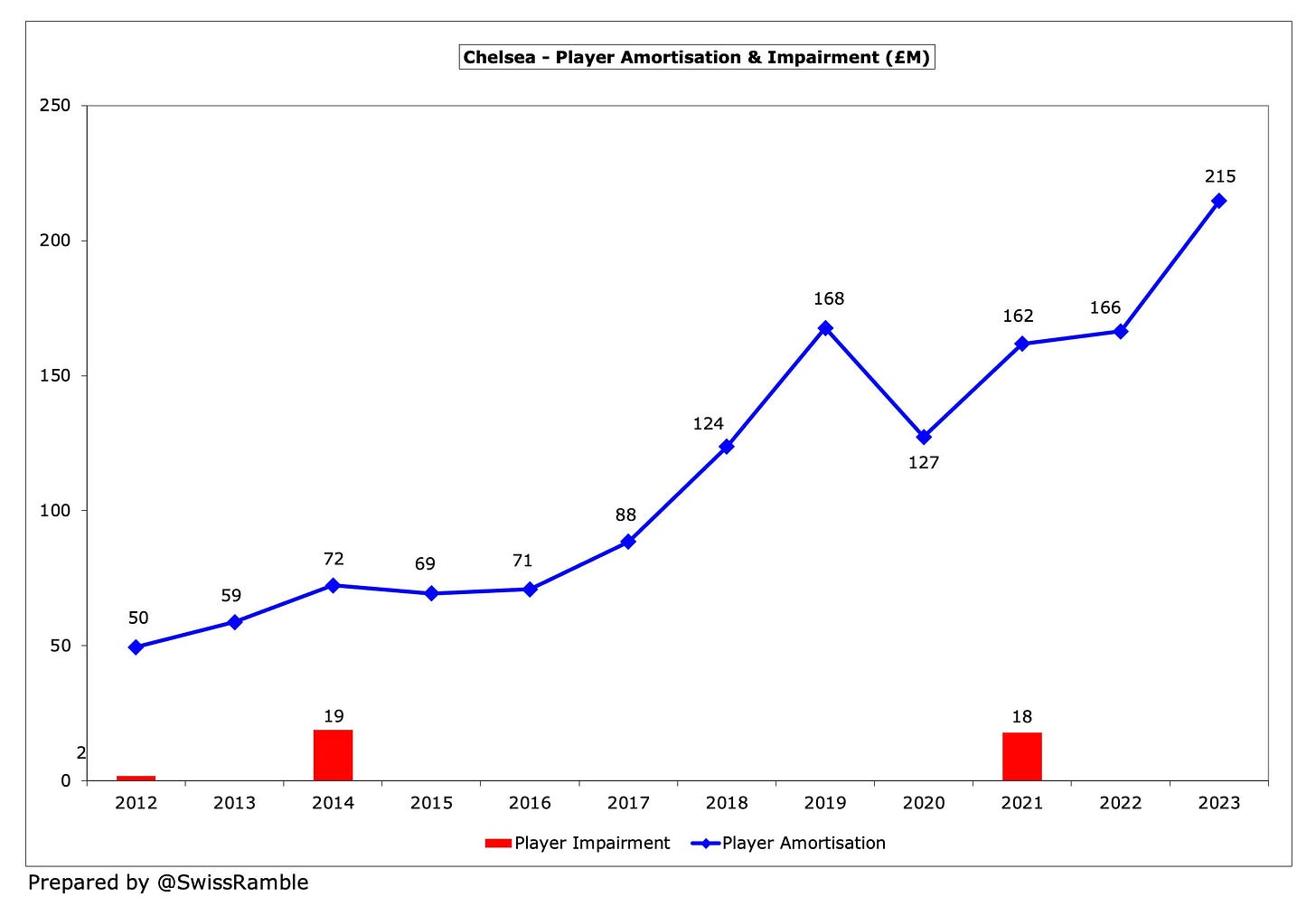

We all know that Chelsea have spent a lot of money, both in the summer and in January. The club obviously decided on long-term contracts as a means of mitigation, spreading the fees over a much longer duration and keeping the yearly amortisation fees under control. We’re still talking about a large amount of money, as Chelsea already had the highest amortisation fees for a Premier League club in 2021. Swiss Ramble did an excellent breakdown of the finances on this (as one would expect). Chelsea’s amortisation fees look to be higher than ever, even as the long contracts stop things spiralling out of control.

Chelsea are also buying into amortising these deals for a long time. Tomkins’ Law of transfers dictates that, on average, only 40% of signings work out. In contrast to some of their summer moves, Chelsea specifically went young in January. This has a much greater upside. If, say, David Datro Fofana ends up becoming a superstar, Chelsea got him under a controlled financial model, and he’ll be tied into some low wages for many years. Just in terms of probability, you’d bet on at least one of these young players really exploding, and a rising tide can lift all boats. Chelsea have taken punts on a group of young players, with the potential for huge returns.

At the same time, when some of these players inevitably don’t work out, the Blues could be paying for them for a long time to come, with contracts that could be difficult to shift. This is certainly a gamble, and one I’m not completely sure Boehly understands.

Boehly is bringing a baseball framework to football. I’ve never watched a single baseball game in my life, so I might be talking bollocks here. But the skills to succeed in baseball are primarily about individuals. Obviously, dressing room dynamics are a factor, but if you’re good at baseball, chances are you will succeed on a team. The number of variables in signing the right footballer are orders of magnitude greater. You have to find the right player and the right fit for the role and system. It’s much harder to be sure of any transfer succeeding.

Chelsea bought three players last summer who I would describe as “win now” signings: Raheem Sterling, Kalidou Koulibaly and Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang. None of them have done what they were brought in for. I don’t think we should be totally shocked about this. Aubameyang was clearly declining over his last 18 months at Arsenal, and a hot streak at Barcelona doesn’t change that. Sterling’s situation was less terminal, but his last two seasons at Manchester City were far from his best, and we can no longer just put it down to Pep Guardiola’s tactics. Koulibaly was slightly more of a surprise, but he’s 31 years old while moving to a faster and more physical league. These things happen. The January moves definitely look like a correction in this sense. Chelsea acknowledged that the peak-age signings flopped and have moved hard towards targeting younger players.

The plan right now, as far as I can tell, is to sign the best young players on the market, maybe taking more risks than other clubs, and have Graham Potter coach them into excellent senior professionals in a coherent system. David Ornstein reported this week that the club are totally behind Potter, believing he should be judged over years rather than months. Hiring Christopher Vivell as sporting director makes sense there. He’s a scout that got promoted up through the Red Bull system. His job isn’t to build an overarching philosophy and strategy the way Ralf Rangnick did at Red Bull, because Chelsea think they already have the pieces for that between Boehly and Potter. His job is to spot talented younger players who can fit into Potter’s tactical framework and the business model laid out by his bosses. He’s a cog in the machine.

So Chelsea’s long-term success lives or dies on Vivell’s talent scouting and Potter’s cohesive coaching. I don’t think we can pass judgement on any of the January signings just yet, so that will have to wait. On the other hand, I don’t know what to make of Potter so far. I can’t see many clear patterns of play beyond just stale possession, nor can I see much of a real sense this team is improving. It might all click. I’ve seen managers struggle for some time before their coaching ideas suddenly click in and it all works. But right now, I’m just not seeing it.

Chelsea seem to strongly believe it will turn into something. Boehly and Clearlake’s plan isn’t to spend this kind of money forever. This is almost seed money, used to build a new project that will be profitable in the long run. I’m sure they would have expected top four at the start of the season, but the January spending was obviously about longer-term thinking, in the acknowledgement it will take time.

Boehly likes to reinvent the wheel. He likes to show that he’s found a different and better way of doing it. But right now, I’m not seeing some smart vision here. They’re just betting a lot on young players become superstars. It’s a punt, and one that could pay off big time. If not, Chelsea could be financially constrained paying off these long-term deals for years to come. Only time will tell.

The big challenge with signing young players on cheap long term contracts in football is that in football, unlike in baseball, they will start asking for more money and/or for transfers as soon as they feel that they are underpaid relative to their contributions or to the wages of other players on the team and in their league. The two Mikes touched on this in their podcast. So Chelsea might be forced to spend big to upgrade the contracts of their cheap players (defeating their long term cost control strategy) or sell the players who are actually performing well. It’s a bold strategy, Cotton, let’s see if it works out for Boehly.

Lubo's point about the profoundly different attitude of football and baseball players to long term contracts (not to mention that of agents and clubs) is very well taken, as is Grace's assumption that "chemistry" and interpersonal rleations are significantly less important in baseball.

While "clubhouse cancers" (both real and imagined) certainly exist in baseball, their impact on the field just isn't as pronounced because the game is inherently one of individual battles rather than collective action. The 162 game regular season and six day a week schedule also mean that interpersonal conflict tends to be worked out, or at least defused, rather than festering.

Thus the long tradition of successful baseball clubs that hated each other, be they the "Bronx Zoo" or any of those titleholders characterized by the "25 guys, 25 cabs" school of transport to and from the game.

It was also very instructive to learn that Boehly also engaged in "outside the box", "disruptive" thinking with regard to his day job, while apparently ignoring or downplaying rather prominent red flags.

One question that I have is just how long a leash Clear Lake will allow him if their return on investment isn't what they expect. They are likely to be patient when compared to many traditional owners, but that relative patience isn't bottomless.