Why International Teams Don’t Play the Way You Expect

National teams have the shortest blanket of all

Note: I will not be passing judgement on any of the teams or managers mentioned in this newsletter. I have various criticisms of all of them, and I don’t think any are having a spectacular Euros so far. But, as an article of good faith, we’re going to assume they’re all doing a good job and making wise decisions with the players they have available. This article isn’t about good or bad, it’s just about choices.

England are boring. Everyone knows it. On paper, it doesn’t make sense. This team has used Harry Kane, Raheem Sterling, Phil Foden, Mason Mount, Jack Grealish and Bukayo Saka in attack. Maybe those aren’t the players you’d pick, but we can all agree they’re no slouches nonetheless. And at the back, it’s John Stones and Tyrone Mings in front of Jordan Pickford. No offence to those players, but they’re not of the same calibre as those going forward.

Legendary former player and less legendary manager Jürgen Klinsmann couldn’t make sense of it. “You have to send out your team based on your strengths”, he told BBC in his capacity as a pundit. “And when I see that England squad, the strength is the attack. It’s going forward. I mean, these youngsters, it’s like they’re Mustangs, you gotta let them go. And that’s what I hope for.”

Germany, on the other hand, are downright gung-ho. They have been throughout Joachim Löw’s tenure, and they were back when Löw was still assistant to Klinsmann. When Löw, Klinsmann, Bierhoff and others transformed the Germany setup, it was all about throwing out the old methods in favour of this new, exciting, proactive style. Klinsmannism was all about throwing out the defensive style, so it makes perfect sense that he looks at England’s talent and thinks “attack, attack, attack!” It also surely doesn’t hurt that he was one of Europe’s most prolific strikers at his best, while Gareth Southgate was a solid and reliable centre back.

Löw is one of two managers at Euro 2020 to have won the World Cup. The other, Didier Deschamps, couldn’t be more different. His France team are, to borrow a line from friend of mine and CBS Sports editor Mike L. Goodman, “so good they don’t need to attack”. Deschamps’ first tournament in charge was the 2014 World Cup, where they didn’t have all the pieces they needed but actually played some decent stuff. They had Yohan Cabaye pinging balls everywhere from the base of midfield, with Paul Pogba and Blaise Matuidi shuttling in front of him. The front three, in the absence of Franck Ribéry, eventually settled on Antoine Griezmann, Karim Benzema and Mathieu Valbuena. That’s a fun team, and they played some good stuff.

But from 2016 onwards, Deschamps has always had more talent than everyone else. This meant he didn’t have to get all his best players on the pitch in order to put out a good side. He could, with some justification, drop Benzema over disciplinary issues without costing an awful lot in overall quality. They were still one extra time goal away from taking the whole tournament to penalties.

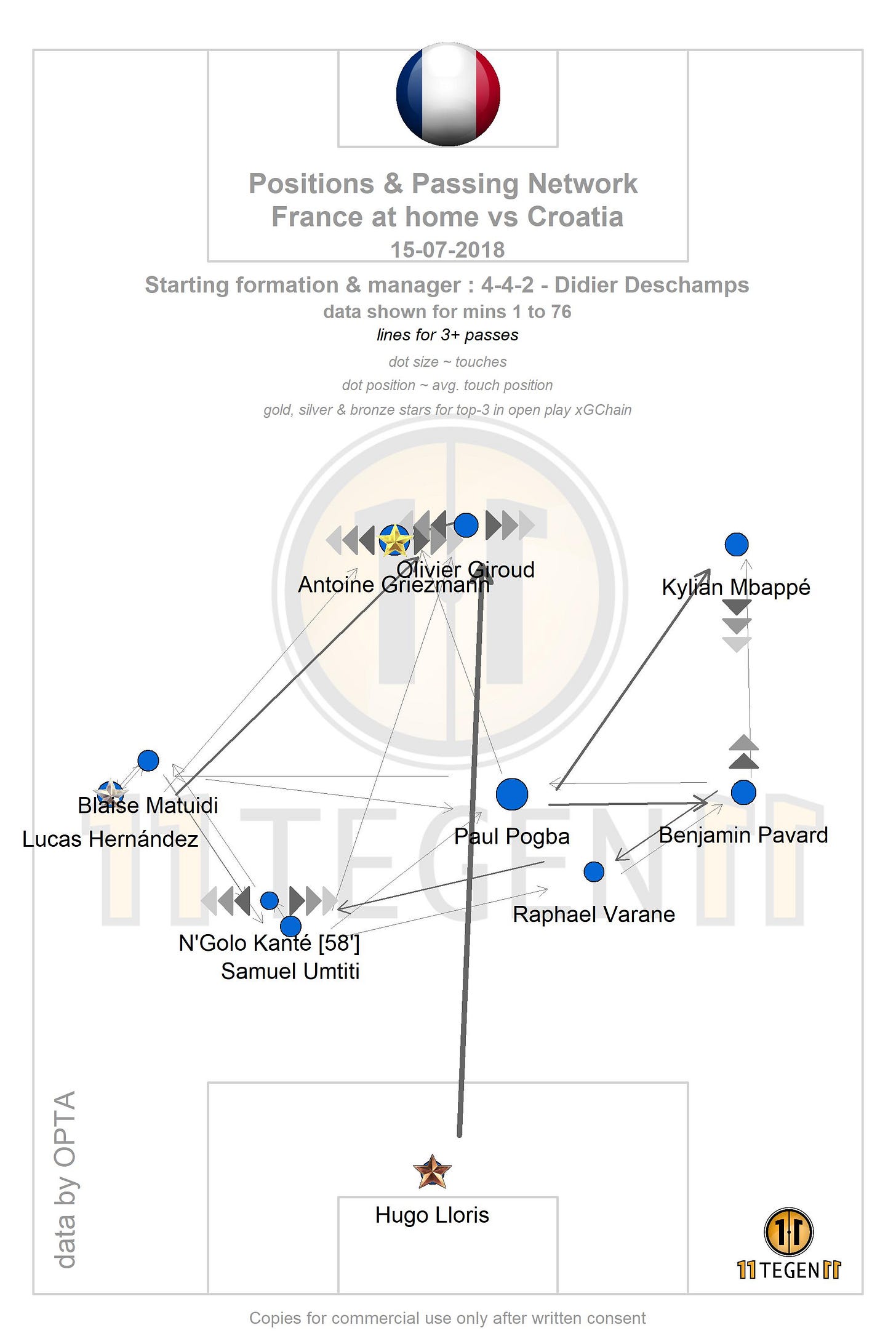

In 2018, he went even more defensive. The passmap from the World Cup final, one of the two greatest days in the history of French football, says it all:

The tactics were the sort you might expect at an English non-league game: get men behind the ball, knock it up to a big striker, and have good players running off him. Those players running off the target man just happened to be Kylian Mbappé and Antoine Griezmann. The aim seemed to be to play defensive, long-ball football, but with the best players in the world.

Deschamps didn’t “send out his team based on their strengths” at all. He did the exact opposite. He knew he wanted to cover up the weaknesses and trusted he’d still have plenty going forward to compensate. He was arranging his short blanket in a way that would keep the coldest part of his body warm, knowing that the rest could cope with the cold.

The short blanket metaphor was introduced to English football through either Rafa Benítez or José Mourinho. It’s unclear who said it first, but that’s irrelevant. The quote originates with Brazilian former player and manager Elba de Pádua Lima, better known as Tim. Having had a lengthy career that probably peaked with the 1968 Campeonato Metropolitano win at San Lorenzo, Tim might be virtually unknown outside of Portuguese and Spanish speaking countries. But his “short blanket” metaphor might be the clearest description of football’s innate challenges anyone’s ever come up with. I can’t find his full quote translated into English, but it’s essentially this:

“Football is like a short blanket. If I cover my head, I uncover my feet, and vice versa”.

Löw’s Germany have used their short blanket to cover the attack completely, even if it leaves the defence exposed. Hungary’s second goal was almost comical from a defensive perspective. Within a minute of scoring, Manuel Neuer and all their defenders are done by a couple of straightforward chipped balls no one bothers to defend properly. It’s incredibly careless. That might have been a moment to calm down, get to grips with the game and then, slowly, push for a winner. But nope! On the other hand, they threw so much at it to get that equaliser and were able to really turn it on.

If Didier Deschamps or Gareth Southgate managed Germany, they might have seen out a frustrating 0-0 draw in which the side struggled to create good chances but managed to get through with a drab point. It might not have been better or worse (though obviously it might), it would have just been different.

England against Germany on Tuesday might turn out to be the perfect expression of this. I’m not for the life of me going to predict the result. But the pattern of play seems clear to me. Germany will dominate possession and look to get their good players on the ball, pushing up high and switching the play quickly to the wing-backs. England, in exchange, will get behind the ball and look to launch quick transitions. We see this type of clash all the time at club level, but it’s usually big club against small club, good players vs less good players. This time, you’re talking about two teams with comparable talent. If the managers swapped places, I’m sure England would be dominating the ball and looking to attack a compact Germany.

Löw and Southgate have similarly sized blankets and use them very differently. At club level, it’s possible to make your blanket bigger. When Liverpool signed Virgil van Dijk, they could really set the full-backs loose, and trust the blanket was large enough to still protect their own goal. International sides don’t have that option. Löw has Mats Hummels at centre back who clearly can’t do everything he once could. Southgate has John Stones who just had the best season of his career at Man City, but he’s still got a mistake in him. Löw responds to this problem by throwing caution to the wind and accepting this weakness in exchange for Germany’s good attack. Southgate responds to it by reining his team in and making sure his centre backs are properly protected, even if it takes something away from the attack.

Having good attackers doesn’t mean an international side will do lots of attacking. Having good defenders doesn’t mean they’ll have an impenetrable defence. There are many different ways to tip the scales. The ingredients are not the meal here. While we can argue all day about right or wrong choices, all these teams are working with compromises, and they’re all finding their own solutions.