This is the fifth World Cup Flashback, a series looking at the tactics and approach of every World Cup winner since 1990.

When Germany hosted the World Cup in 2006, they wanted to show a different side of the country to the planet.

For decades, international perceptions of Germany had been shaped by World War II-era stereotypes and negative attitudes. The 2006 World Cup was Germany’s first event of this scale since reunification 16 years earlier, and it was a big chance to show off the country that many of its citizens believed it to be: modern, forward-thinking, and inclusive. The official tagline for the tournament was “a time to make friends”. How sweet is that?

In that sense, they smashed it. Germany felt a new confidence in itself as a nation. Other countries known for anti-German feelings started to see that things had changed. That was certainly the case in England, and I’d have to assume it was the same for another country that considered Germany its biggest football rival: Italy.

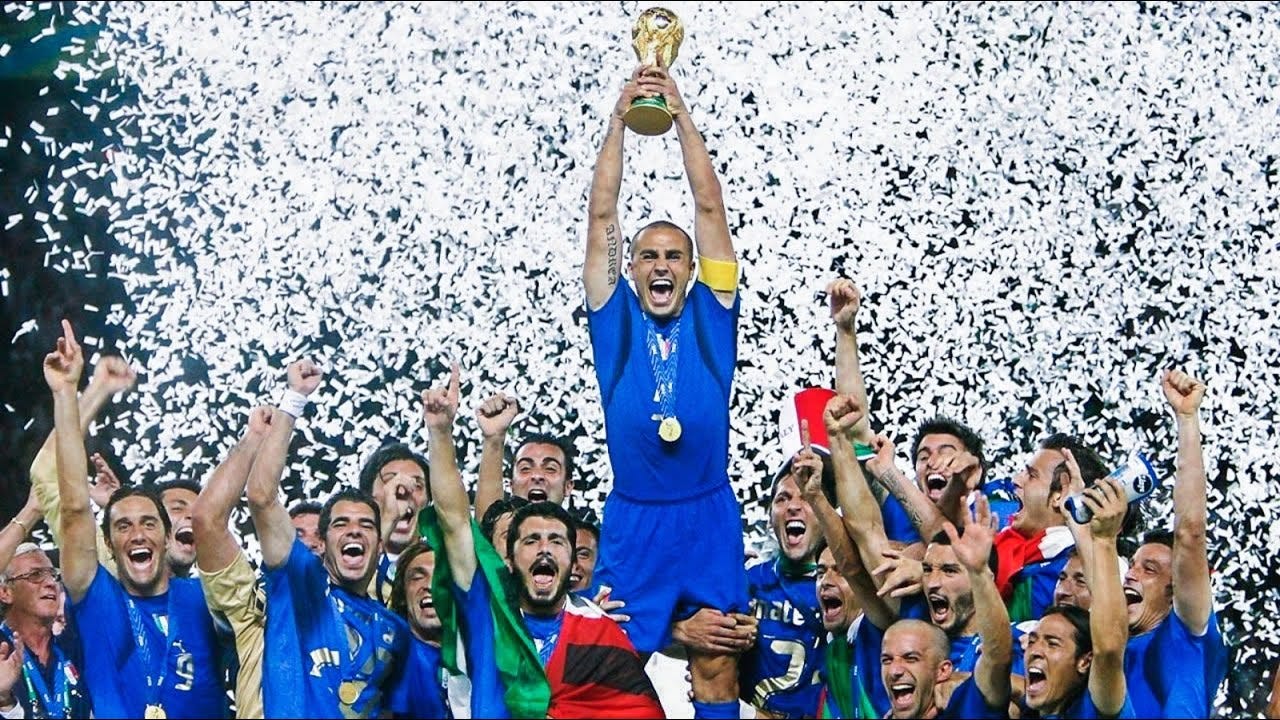

This was not supposed to be a golden era for Italian football. Serie A, by far the best domestic league in Europe during the late 1980s and most of the 1990s, had suddenly fallen behind Spain’s La Liga and England’s Premier League. The national team, too, had been something short of great. The Azzurri lost the Euro 2000 final on the golden goal rule and had slid backwards since, falling to South Korea in the Round of 16 at the 2002 World Cup, then getting going home at the group stage in Euro 2004. The Italians had fallen to 13th in the FIFA rankings. The “smart money” was on Italy suffering another disappointing early exit. While the Azzurri had three World Cup titles, only one had come since World War II, and that didn’t look like changing.

To make matters worse, at the very same moment, Italian football was blowing itself up in a corruption scandal. Half the squad were potentially seeing their clubs relegated from Serie A. And yet it didn’t matter. “I had a fantastic group of players”, manager Marcello Lippi claimed. “In a way, the Calciopoli scandal helped the team to become even more united.”

As for Lippi himself, he had all the experience one could ask for. A five-time Serie A winner, he was probably best remembered (before 2006) for the Champions League-winning Juventus side that could make life a nightmare for opponents. Italian managers, unlike those from most other countries, are expected to be able to coach a variety of different playing styles, and Lippi is no exception. “He worked before, during and after the revolution brought by Arrigo Sacchi”, James Horncastle explained. “His teams knew how to man-mark and to play zone. They invited opponents onto them and counterattacked but could also take the game to whoever they were playing and press them in their half of the pitch. Balance was everything. Lippi's starting XIs were never fixed. They were always in discussion and would be adapted according to the opposition.”

Even if this hadn’t been a successful time for Italian football, the players at Lippi’s disposal were very good. The eleven for the first match against Ghana was pretty star-studded. Juventus’ Gianluigi Buffon, just 28 years old but already over a decade into his senior career, was the goalkeeper. Fabio Cannavaro (32, Juvenus) was the captain and lynchpin centre back. For reasons we’ll get into, Alessandro Nesta (30, AC Milan) has been forgotten a little bit in the years since, but he was absolutely seen as one of the world’s best centre backs at this time. Cristian Zaccardo (24, Palermo) would probably prefer to play at centre back, but he was the kind of old-fashioned defender who could happily do a job on the right. Fabio Grosso (28, Palermo) was a reliable choice on the other side.

Italy used a diamond midfield. The regista at the base of the diamond was who else but Andrea Pirlo (27, Milan). We all know what he could do. To get the best out of Pirlo, you really needed two box-to-box options in front of him, and Italy had that with Daniele De Rossi (22, Roma) and Simone Perrotta (28, also Roma). In the trequartista role at the tip of the diamond was the team’s biggest star: Francesco Totti (29, Roma, but you already knew that). Totti had some injury troubles in the run-up to the tournament, but Lippi viewed him as absolutely essential, so he started. Alberto Gilardino (23, Milan) played upfront, and had scored more Serie A goals across the last three seasons than anyone else. He wasn’t the top scorer in the most recent season, though. That honour belonged to his Azzurri strike partner, Luca Toni (29, Fiorentina). Toni was a classic late bloomer, bouncing between divisions until he caught fire at Palermo before earning a move to Fiorentina. This team had firepower as well as solidity.