Another Brick in the Meat Wall

Set Pieces are changing the Premier League in front of our eyes

Last summer, Brentford did something no other Premier League club has ever done or, likely, would ever have thought to do.

Manager Thomas Frank had left the club to join Tottenham, meaning someone new needed to be hired. Being Brentford, they avoided the obvious names and made an internal appointment.

The assistant manager? Good guess, but no, Claus Nørgaard also left the club to take over as manager of Vejle Boldklub.

A senior player who had the respect of the dressing room? Wrong again.

Brentford promoted the set piece coach to the role of manager. They hired Keith Andrews, probably otherwise best known for playing in midfield at Sam Allardyce’s Blackburn. Even the most dedicated Premier League viewer could be forgiven for forgetting he existed.

Meanwhile, about ten miles Northeast of Andrews’ current job, another former Brentford set piece coach is playing a big part in putting Arsenal at the top of the table.

Something is happening.

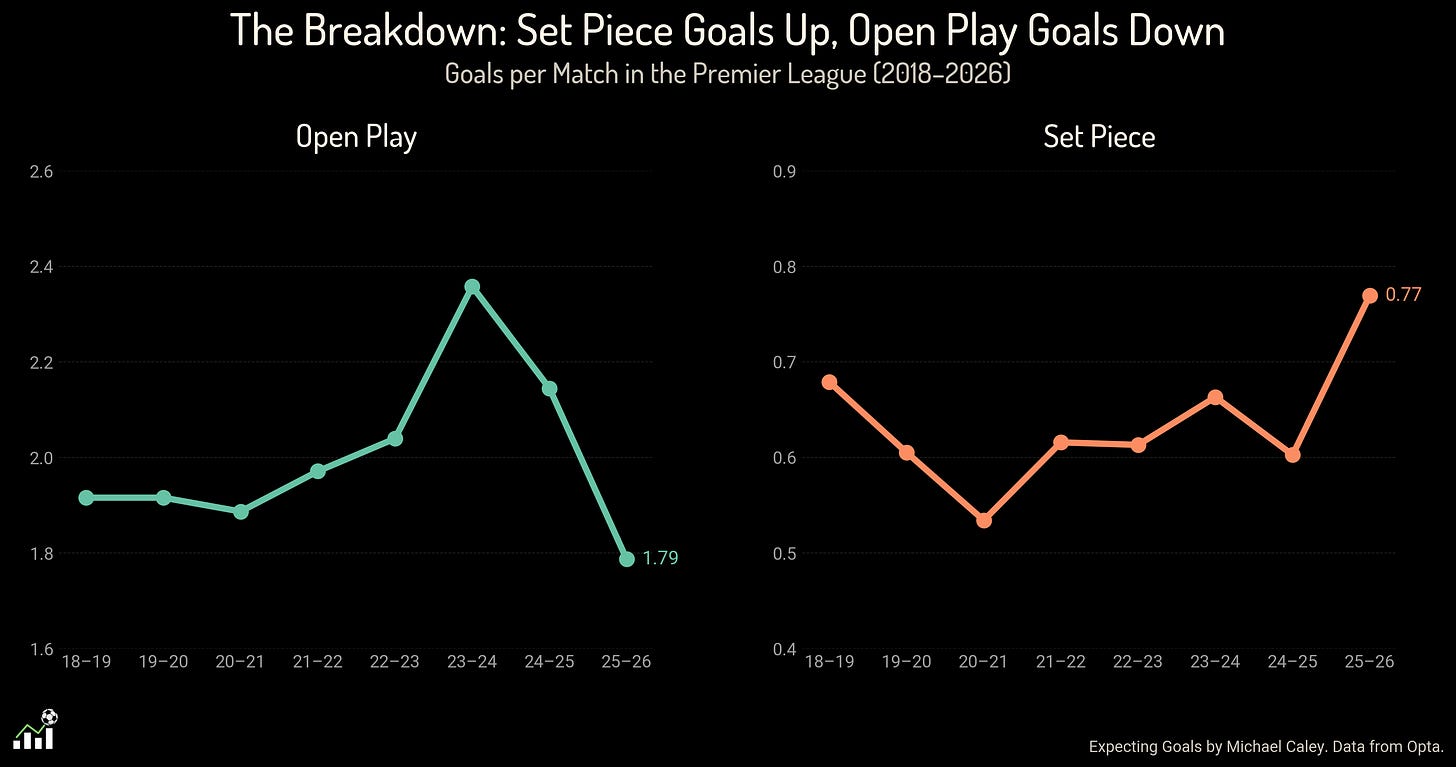

Everyone’s talked about the number of set piece goals this season. I don’t need to tell you that more of them are going in, but here’s a nice graph from Michael Caley, from his amazing study on the matter that informed basically all my thinking here.

Not all set pieces are equal here. As Caley notes, free-kick goals are actually down this season. What we’re seeing is two specific kinds of set piece goals. The first is long throws. A pretty minor concern a couple of years ago, teams are now throwing the ball straight into the box at will when they get a chance to. It is very on trend that when you get a throw-in within the final third, you use that as a set piece rather than a quick restart.

The other kind of set piece is really an evolution on an existing part of the game. Teams keep taking a very specific corner: play an inswinger right into the six-yard box, and crowd out the goalkeeper with as many of your players as possible. Obviously, putting the ball closer to the goal is a good idea, but only if you can take the ‘keeper out of the equation. Teams have found an answer to it: a lot of attackers in the way. Flood the zone. Or, as it’s colloquially known now:

The Meat Wall.

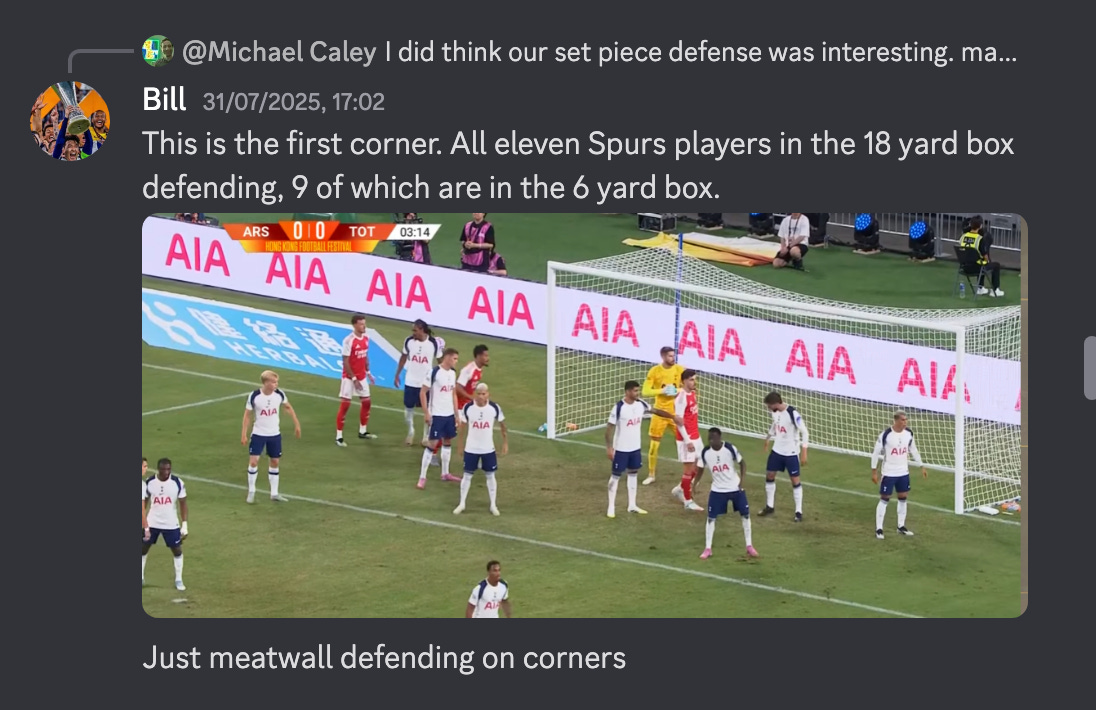

Fun story: this term was first coined on the Trivote Discord server (which you can join here!!! Unless you’re my dad, then no, you can’t). Bill described Tottenham’s preseason defensive corner shape as “meatwall defending”.

At some point pretty quickly afterwards, the term started being used to describe attacking corners seen more often at Chelsea and Arsenal. Caley published his study and deliberately avoided the term, but he did a podcast episode talking about the new approach as the “meat-wall”. Jonathan Norcroft of the Sunday Times was apparently listening and gave us this two-page spread.

So that’s it. It’s the meat wall now. It’s stuck, and as a tactic, it seems to be doing a great job of putting the ball in the net.

There are two main schools of thought on what this all means. The first is easier to swallow: it’s just a new tactical trend. Plenty of people working in football think this way. “Five years ago”, now-former Nottingham Forest manager Sean Dyche said a few months back, “people were going “why do you rely on set pieces?” Now they’re in vogue. That’s just the way it goes, it’s just the cycle. Skinny jeans, flared jeans, skinny jeans, flared jeans.”

There’s probably some of that, but at the same time, these are huge changes in the numbers. This isn’t a gradual thing, like the rise of pressing or short passing. It’s a big leap that suddenly happened this season. Skinny jeans didn’t take off one day and die overnight like the meat wall and the long throw. We’re watching a different sport to what we were seeing two years ago.

I was trying to think of other changes in the Premier League that seemed to happen very quickly, and something came to mind from the 2000s: ditching the 4-4-2 to play a dedicated defensive midfielder and just one striker. José Mourinho arrived at Chelsea and embarrassed almost every manager in the country just by playing a 4-3-3 shape. “If I have a triangle in midfield – Claude Makélélé behind and two others just in front”, Mourinho said at the time, “I will always have an advantge against a pure 4-4-2 where the central midfielders are side by side”.1 Very quickly, it felt like an extra midfielder was a must for any competitive side.

But it wasn’t a change that came out of nowhere. Arsenal and Manchester United had both been often playing systems we’d today call 4-2-3-1 for a few seasons. And this approach had become standard elsewhere in Europe for a while.

The Premier League changed a lot in the mid-2000s. It got more defensive, more tactically organised, and more physically demanding. We might be going through a similar moment here. In truth, I think plenty of the changes from 20 years ago have been absolute, rather than a cycle. We’re not going back to training fitness and tactics separately. We might not go back on set pieces here.

In fact, this might have already happened in Denmark.

Back in July 2014, English businessman and professional gambler Matthew Benham bought Danish Superliga club FC Midtjylland. Two years earlier, he took over at Brentford, the team he supports and cares about the most. Benham is a big advocate of using data analytics to inform decision-making. While this was employed at Brentford, Midtjylland were to be even bolder, serving as a sort of testing ground for analytics-driven approaches in football. Any nerd with a laptop could produce reams of theory about how football might work. Midtjylland were going to literally do the field work and put it into practice.

So what did Midtjylland do? They focused on set pieces, especially innovative routines. Did it work?

A year after Benham bought Midtjylland, they won the first Danish league title in the club’s history. It isn’t a long history, having been founded in 1999, but that alone should tell you Midtjylland are not exactly giants of Danish football. Obviously, the rest of Denmark took notice. Other teams started trying similar tricks from set pieces, to the point where Danish football is now famous for it. We even see it with the national team. And it’s pretty easy to see where that came from.

“In 2014-15, [Midtjylland] were the only team in the league to crush this particular phase of the game, scoring 25 goals, while three other teams barely cracked ten”, wrote Ted Knutson, who served as Head of Player Analytics at the club during this period. “Three years later, eleven of fourteen teams were in double digits.”

Ok, so one super nerdy team in Denmark won the league by scoring loads of set piece goals, and then everyone else copied. But what does that mean for open play, you might ask? Knutson says he always believed you could simply score more goals by adding good set pieces, while his colleague Marek Kwiatkowski wondered if it might cause trade-offs elsewhere, simply redistributing the goals and ultimately reducing the open play excitement. As of Knutson’s article in summer 2018, the goals just went up.

“Set piece goals per game have gone up by [0.2 goals per game], while overall scoring is up [0.5 goals per game]. This lends weight to the bigger pie hypothesis, and not merely different sized pieces.”

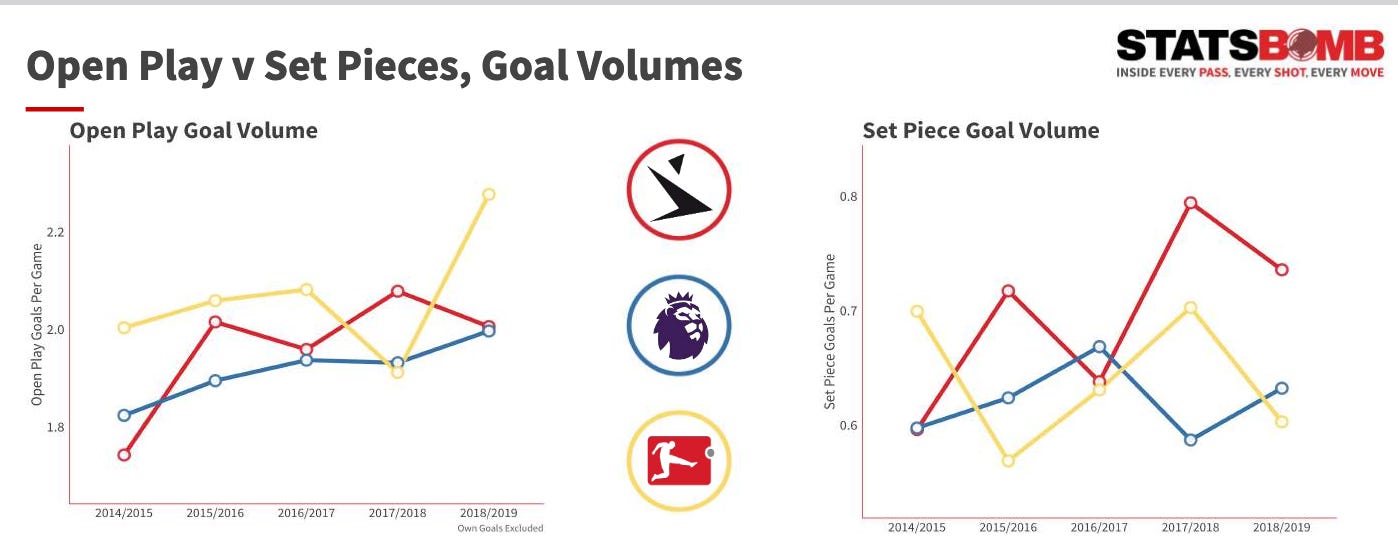

About a year later, Knutson’s company StatsBomb (since sold to Hudl) produced a report for the Danish league organisation into how the Danish Superliga compares to the English Premier League and the German Bundesliga. StatsBomb again found that while set piece goals increased significantly, open play scoring also went up, mirroring numbers from the Premier League (Denmark is in red, England in blue and Germany in yellow).

I do quibble a little with these findings in that the 2014-15 Danish Superliga season was, in itself, unusually low scoring. The rise in set piece goals happened alongside a return to pre-14/15 scoring levels in Denmark. Since this information was published, goals per game declined in Denmark for a couple of years before rising again this season and last. I don’t know why any of this is happening, but it’s interesting, and the overall picture is definitely more complicated than “set pieces go brrr”.

But I think we can see something important from Denmark: you don’t have to stop attacking in open play just because you’re scoring more from set pieces. That is a choice, and it might not even be the optimal one.

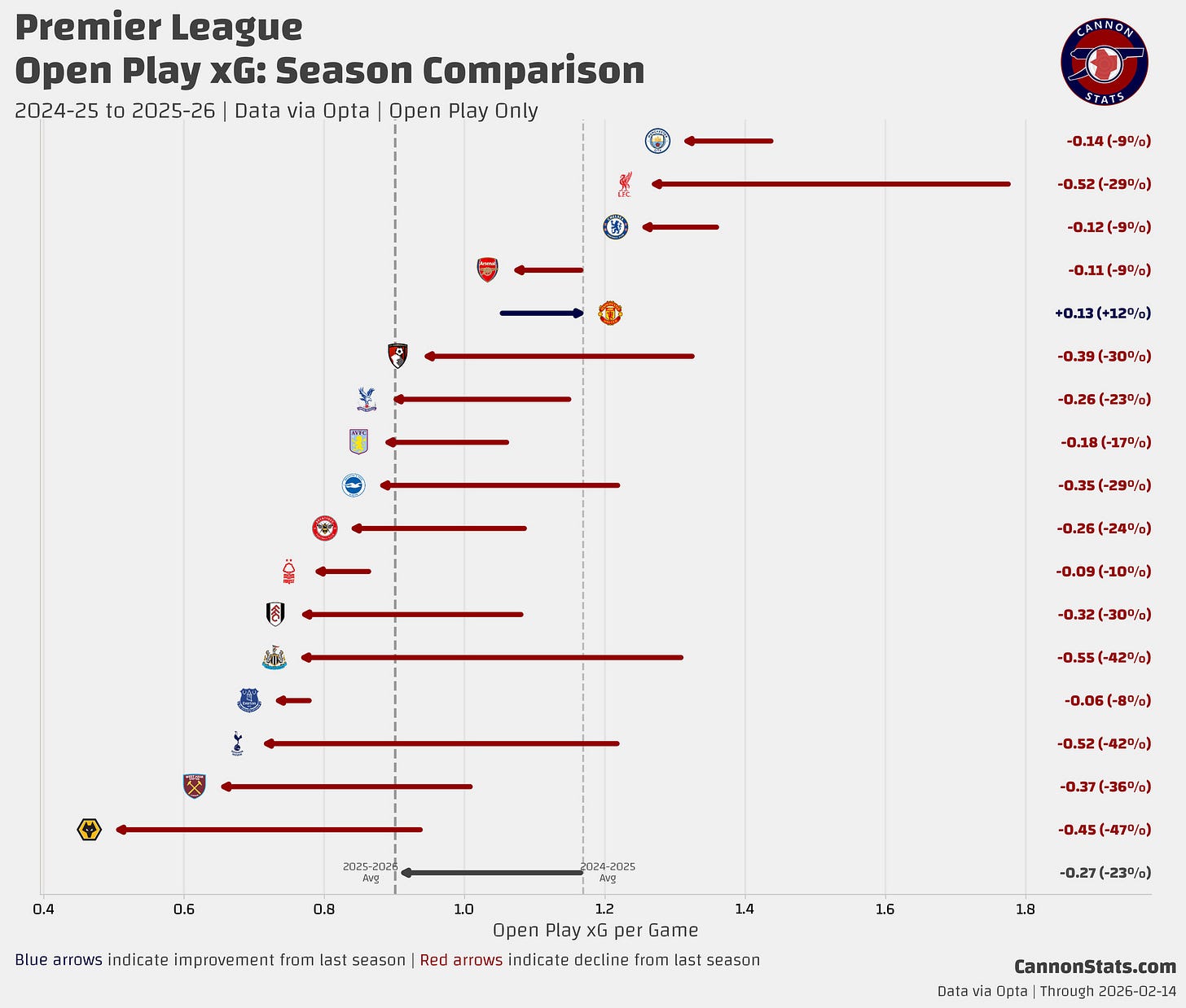

But it’s one that Premier League clubs are making. As Scott Willis showed recently, 19 of the 20 teams are creating fewer expected goals from open play this season compared to last. The entire league has just started playing less football, almost overnight. Managers might be following the data on set pieces, but they’re not particularly analytics-driven otherwise. Mikel Arteta, Pep Guardiola and the rest don’t play a certain style of football because anything in the data told them to. They do it because that’s what they believe in, based on who knows what. Man City’s number crunchers could produce reams of data saying that the team should completely change their style of play. What do you think the reaction would be if some lowly analyst knocks on Guardiola’s door and tells him he’s completely wrong about football because the numbers said so? You and I both know that analyst would be finding a new job tomorrow. Managers are taking fewer risks in open play not because the data says so, but because they believe in it.

(Ruben AmorIN? I kid.)

Perhaps teams can optimise for set pieces and still score lots of goals from open play. They might get worse at both attacking and defending in open play if they spend a lot more time on the training ground drilling set pieces. But I don’t personally think it can be isolated entirely. Clubs will presumably look to sign players better in the air to both attack and defend set plays. If corners and throw-ins are so valuable, teams might start actively trying to win them. And what could that look like? Perhaps they will look to get the ball wider more often (the StatsBomb report did note that more chances were created in wide areas in Denmark). That might mean using wingers who “get chalk on their boots” and play on the same side as their dominant foot. If the ball is going wide more often, teams might see less use for extra central midfielders and players who can thread a pass through the middle of the pitch. And if it’s going wide so often, perhaps it will be a good idea to have another striker in the box, getting on the end of things. Maybe the old-fashioned British 4-4-2 is the system more optimised for a set piece-heavy sport.

Skinny jeans, flared jeans.

That’s a complete guess on my part. Maybe we’ll see football change any number of ways. The point is it will change, for any number of reasons. Personally, I don’t like the rise of these set-piece goals because I don’t really enjoy watching them. It’s not the football I’m here to see. But it’s going to cause all sorts of responses and changes we can’t predict. Let’s check in sometime later and see how teams are adapting to the meat wall, yeah?

Yeah.

Cox, Michael (2017). The Mixer. London: HarperCollins.

yeah I think that’s the main thing, I guess call us purists but the eye test is clear to me: the games are less good to watch.

also the emphasis on set pieces means more of the players (and fans) are incentivized to fixate on the refereeing. now a corner or a throw in even feels much more consequential to the result… to the detriment of the sport as a whole.

and wasn’t VAR supposed to “end” grappling in the box? now if anything I see MORE fouls in the box as players spend more time attacking 50/50 balls nearer to goal

so between the $$$ fueled talent hoarding by the super clubs - meaning more of the rest of the leagues are looking for players who can athletically and tactically compete (but often lack for creativity or technical ability) - and now the emphasis on set pieces, it feels like this year in particular I see much less that sparks joy in the sport I love