The Enshittification of Manchester United

The Glazers sucked the life out of Old Trafford. That was the point.

Hey! If anyone wants to hear more of my thoughts on Jürgen Klopp leaving Liverpool and what’s next, I appeared on the Double Pivot Podcast last week to talk about it with Mike Goodman and Michael Caley. Check it out on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or… I can’t figure out how to do an RSS link to a single podcast episode, but search and you’ll find it.

When Jim Ratcliffe bought Manchester United, everyone understood it as a fixer-upper. United haven’t won a league title in over a decade and that doesn’t look like it’s about to change any time soon. Bad decision after bad decision has defined the club and ensured a downward trajectory. A club of almost limitless potential has been mismanaged in just about every way on and off the pitch. Old Trafford is in a joke of a state, not getting so much as a lick of paint since the Glazer family took over the club in 2005. Even the revenue isn’t as impressive as it “should” be, with United down to fifth place in the Deloitte Money League after finishing first every year from 1997-2004. Everything is bad. This hasn’t bothered the Glazers too much. I think it’s entirely gone to plan.

Manchester United have been enshittified.

Canadian writer Cory Doctorow coined the term “enshittification” in a Wired magazine article in 2023. He used it to describe how tech platforms first thrive and then decay to become, well, shit. It happens in four stages, he claims:

“First, they are good to their users”. This is fairly obvious. Amazon, as Doctorow explained, “sold goods below cost and shipped them below cost” as easily and cleanly for you as possible. Facebook helped you connect with your friends. Google could find exactly what you were looking for online. You get the idea.

“Then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers”: once you’re locked in, to use Doctorow’s term, the platforms don’t need to worry about you anymore. So they shift focus. Facebook pivoted away from showing you what your friends were doing and towards showing you posts from media companies and brands. Amazon started suggesting products that weren’t what you were looking for as much as what would make the most money for Amazon. Netflix started cancelling many of its shows that weren’t pulling in a huge audience, now adding an ad-supporting tier that will inevitably put more emphasis on advertiser-friendly programming. Again, you get the idea.

“Finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves”: after forcing the entire journalism industry to “pivot to video” based on Facebook’s algorithm pushing that concept, the platform flipped the switch and decimated that business, causing many journalists to lose their jobs (and Facebook lied about the metrics, but that’s a story for another day). Google made every website on the internet prioritise SEO (search engine optimisation) to get to the top of the search results, then started providing more information within the search page, to keep users and the ad revenue they create on the platform instead of visiting someone else’s website. You’re on the internet. You’ve seen this one.

“Then, they die”. In theory, anyway. This one almost seems more optimistic to me than the alternative, when we’re trapped on platforms creating zero value that continue to dominate in a zombified state forever. But even if it takes a very long time, it’s certainly the endgame of a business engaged in extracting more and more value from a company shrinking and declining in cultural status and relevance, which will eventually leave nothing left to take out.

The Glazers bought a football club very much in stage one of this plan. The “users” in this case are the fans, and no one had enjoyed their football from 1992-2005 or so more than United supporters. Alex Ferguson oversaw football excellence, in the process building a large new fanbase and “locking in” those consumers. That’s what made it the best possible football acquisition at the time. United were a revenue machine that arguably hadn’t been fully exploited.

The purchase had been highly controversial due to the “leveraged buyout” that saw the Glazers buy the club on borrowed money and load that debt onto United itself. The main shirt sponsor, Vodafone, decided it no longer wanted to be associated with a club run by the Glazers in that manner. This was supposed to lead to commercial disaster, but quite the opposite happened. “[Joel] Glazer was thrilled”, Joshua Robinson and Jonathan Clegg explained in The Club, their book on the business history of the Premier League. “He didn’t think a telecommunications company had any business being a global shirt sponsor anyway. That sector was more suited to regional deals, he explained. [Chief Executive David] Gill had never heard the strategy presented that way. But soon he would see it in action every day as Manchester United spun its NFL sponsorship know-how and chopped up the market into as many pieces as possible”.

And so, with the fans “locked in” after years of success, United could prioritise all those commercial partners. This had relatively little impact for several years. Ferguson was making the football decisions, and he was largely untouchable. But once he and Gill both retired at the same time, the Glazers put Ed Woodward in charge. Woodward was nothing if not their man, having advised the late Malcolm Glazer on buying the club during his days as an investment banker before joining the organisation. And when he was in charge of all decisions, Woodward really prioritised step two on the enshittification path.

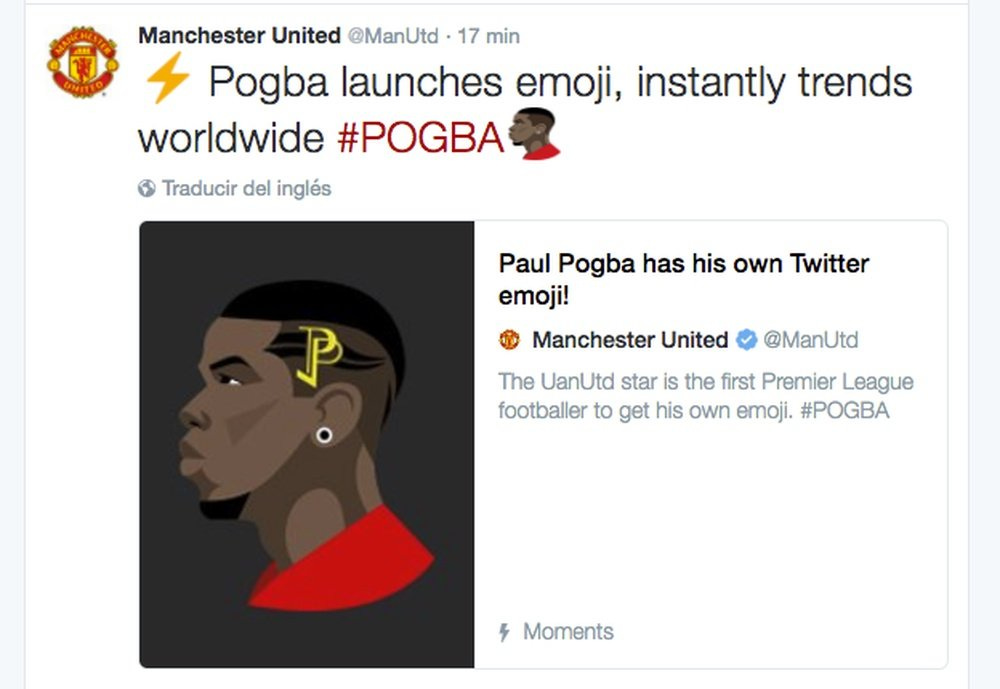

That meant prioritising the commercial partners over everything else, namely sporting success. We know the kinds of players I’m talking about: Radamel Falcao, Zlatan Ibrahimović, Paul Pogba, Alexis Sánchez, Cristiano Ronaldo. I’m not saying all of these were clearly the wrong signings from a sporting perspective at the time, and that’s actually key to the story. “Nobody sat down and said, 'Let's make Google worse’”, Doctorow explained. Equally, no one at United said “let’s give up on winning titles”. But Woodward and his team absolutely thought “he’ll be great for the marketing, let’s get him” before prioritising the sporting outcomes. There was at least some sporting logic to signing all of those players, but the primary driver of these decisions was marketing potential.

None of these were genuinely good marketing decisions. As far as I’m concerned, by far the best way to grow your commercial revenue is to win lots of football matches, in the process appealing to new fans and establishing new star players. Mohamed Salah was not a global superstar when he signed for Liverpool, but he became one by playing very well and helping the team win games. United’s commercial revenue grew by 37% between 2014 and 2022, less than the 62% increase at Chelsea, 84% at Arsenal, 86% at Man City (no comment), 124% at Liverpool and 325% at Tottenham1. United’s commercial strategy has not been more successful at its stated goals.

But it’s certainly much easier to do if you lack football expertise. Building a quality football team is very hard, but anyone can sign famous players. That’s why Louis van Gaal called United a “commercial club” rather than a “football club”. It doesn’t mean that they don’t care about the football side, just as more sporting-focused clubs still worry about the commercial side. Every club cares about both. But United have come at it from a point of view that the commercial revenue will drive sporting success rather than vice versa. When given a direct choice, they have prioritised the former over the latter, to the long-term detriment of the former.

But that’s ok because United were heading for stage three of enshittification regardless. The club began paying out shareholder dividends in 2016. The Glazers owned 69% (nice) of the club at this point, so it was obvious where the bulk of this money was going. United have been the only Premier League club to regularly pay out dividends, averaging £22-23m per season from 2016-22, more than any individual player’s salary, along with another £20m or so on interest payments each year. I wish I understood all of this as well as Swiss Ramble, but I do not. The point is the club’s primary concern was now neither sporting success or commercial growth. It was acting as a bank for the Glazers. If United could not grow as fast as other clubs due to incompetent management, then the Glazers could always simply extract money out of the club, milking the cash cow for as long as they can.

And it worked because there was absolutely no way of stopping them! That’s probably why they bought United in the first place. Don’t take my word for it, take the word of Joe Ravitch, founder and partner at The Raine Group, the investment bank that among other things, brokers major sales of European teams, most notably Todd Boehly et al’s purchase of Chelsea. “The big difference with European clubs to US clubs”, Ravitch explained recently, “is they’re not a franchisable league. You can be a jerk and there’s nothing they can do because you own your IP, you own your club. And you can do as much as you want with it outside of playing the league games”.

I think Ravitch makes some claims that are just wrong (he seems to believe clubs have “more fans in Japan than in England”, a fiction made up by marketing departments). But he’s an extremely high-level person involved in top football club sales and this is what he’s saying to potential investors. This is how the finance people around football view the sport. And yes, his company did just oversee the sale of 25% of United to Jim Ratcliffe, so you can bet Ravitch said all of this to him, too.

Ratcliffe and INEOS’ job, then, is to deshittify, or unshittify, or whatever the correct word for that would be, Man Utd. Because you know what the next stage is. “An enshittification strategy only succeeds if it is pursued in measured amounts”, Doctorow says. “Even the most locked-in user eventually reaches a breaking point and walks away, or gets pushed”. I don’t know if that’s true for football clubs the same way it is for tech platforms. You can do almost anything to a club and you’ll still have a large number of supporters spending money every weekend because our dumb primate brains crave that emotional bond we’ve formed. Ravitch is right that you can be a jerk.

The best news is that Ratcliffe has a legally binding agreement that the Glazers will not take any dividends for the next three years, while INEOS reportedly don’t intend to add any more debt onto the club. The Glazers got their big payout by selling 25% of the club, which apparently keeps them from “needing” to take out dividends for these three years. After that point, they probably have an eye on selling more of the club, be it to Ratcliffe or another investor. High interest rates have made it much harder to get big deals like this done, and that’s probably a factor in deciding to sell just a quarter of the club, instead of the whole thing. If the investment climate is better in three years’ time, you’d have to think more of Man Utd will be sold.

It shouldn’t be that hard to make better decisions at Old Trafford. They can sign better players, provide the squad with better coaching, and put a clearer long-term strategy in place. But it requires patience from all involved. Enshittification really sets in when companies prioritise immediate gain. “Individual product managers, executives, and activist shareholders all give preference to quick returns at the cost of sustainability, and are in a race to see who can eat their seed-corn first”, Doctorow says. Signing Alexis Sánchez and giving him a snazzy announcement video provided a quicker marketing opportunity than a younger player with more upside would have, even if that player became a superstar in the future.

United have already enshittified enough that the long-term target is probably to be one of the teams competing at the top (yes, I know about Man City’s finances). It’s hard to see how Ratcliffe could make them the unmistakable “biggest club in the world” again. The Glazers might have permanently sucked potential out of the football club. It shouldn’t be nearly this bad going forward, but the golden era is not about to come back. United have been enshittified into being a normal football club. They best hope it does not go any further.

I am aware that Man Utd saw a decent increase from 2022 to 2023. But since Man City are the only other Big Six club to have reported their numbers from 22/23, and also saw a healthy rise, we can’t yet say if this is United commercial strength or the big clubs as a whole.

“[Doctorow says]… ‘Even the most locked-in user eventually reaches a breaking point and walks away, or gets pushed.’ I don’t know if that’s true for football clubs the same way it is for tech platforms.”

Some of them have walked away, to be fair:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/F.C._United_of_Manchester?wprov=sfti1

Great stuff Grace. Radcliffe always struck me as a bit of a chancer, so if I were a Utd fan I'd not have a huge amounts of confidence in it being significantly better. Better, maybe but only by degrees. But the thesis is sound: as a Chelsea fan were at stage two. We've become a 'finance club'. Of course Clearlake want to win on the pitch but they're finance people who see things through a financial lens. And whilst winning is a very good way to make money, my own worry is they'll see the massive chunk of prime real estate as being the easiest route, with Chelsea Pitch Owners and easier problem to solve than the on pitch related ones that are stacking up. How depressing.