Hi everyone, Grace here. I know I’ve been slow at putting out newsletters over the summer, but hopefully, this 6.5k word tome will help make up for that. I’m finally returning to the World Cup flashback series with an entry on Germany in 2014.

Substack tells me this newsletter is too long, meaning email inboxes will cut off the last chunk. It looked ok to me when I tested it out, but if the newsletter just ends suddenly, try reading it on the web or in the Substack app for the full version.

The year is 2014. Here is the state of play.

Noted nice guy and beacon of honesty Sepp Blatter is still in charge FIFA. In his big plan that definitely didn’t have any corruption involved to spread the World Cup around, he’s running a policy of rotating the host nation between different continents. Asia got the gig in 2002, followed by Europe in 2006 and Africa in 2010. South America is up next. What Blatter needs is a country with enough history in the sport to sell to the world, but enough corruption to really make a huge profit with baffling infrastructure choices and political favours.

He’ll get one.

Brazil become the frontrunners to host the tournament pretty quickly. Argentina, Chile and Colombia all floated the idea but backed out, which was almost certainly the right call. FIFA needed twelve world-class stadia – requiring seven brand-new builds alongside five renovations – three of which are barely used today. FIFA even made Brazil reverse a law banning the sale of alcohol at football grounds in order to please their key sponsor, Budweiser. Many in the country were furious and responded with angry protests against all of this lavish spending in a country struggling to help its citizens.

The ruling Workers' Party was nervous. This World Cup was looking very dicey off the pitch. The actual sporting contest needed to be spectacular. They needed a World Cup and, crucially, a Brazil national team campaign that would redefine the country and live in the hearts of millions for a generation to come.

They’ll get one.

(Thanks to my friend Jeremy Mongeau, whose bit I blatantly ripped off here.)

Brazil were just about everyone’s favourites. Betfair gave the hosts an implied probability of 23.3%, but others thought that too conservative. “No country has beaten Brazil on its home turf in almost 12 years”, according to Nate Silver at the time. “To find a loss at home in a match that mattered to Brazil — in a World Cup qualifier, or as part of some other tournament — you have to go back to 1975, when Brazil lost the first leg of the Copa América semifinal to Peru […] Brazil is the betting favourite to win the World Cup — but perhaps not by as wide a margin as it should be”.

That didn’t deter a quietly confident Germany. It had been a long journey to get here. Germany last won the World Cup in 1990, in their last outing under the name “West Germany” before reunification. That was the old country winning in the old style for the last time. A European Championship win six years later kept the good feeling going for a while, at least. But after that, it had been tough. Croatia sprung a surprise in the 1998 World Cup by beating Germany 3-0 in the quarter-final stage. The team crashed out of Euro 2000 at the group stages. Reaching the World Cup final in 2002 looked great, but it was about an easy path more than anything. Another humiliating group stage exit at Euro 2004 proved the team wasn’t up to much. Something had gone very wrong in the country’s football.

The old methods had grown stale. German football still favoured a sweeper and man-marking scheme long after those methods had been ditched elsewhere. “The national team”, Raphael Honigstein explained in his book Das Reboot, “remained shackled to their libero, a tactical concept that also betrayed the country’s disconcerting longing for an omnipotent Fußballgott who’d organise the defence, lead the midfield and score the odd decisive goal as well”. The mistake had been set in stone decades earlier. “The 1974 World Cup Final pitted [Franz] Beckenbauer, the 1972 Ballon d’Or winner, against Johan Cruyff, the 1973 Ballon d’Or winner”, Michael Cox wrote in Zonal Marking. “The two captains were the world’s two best footballers and essentially dictated their nation’s footballing approach for the next couple of decades: Germany’s man-marking with a sweeper versus Holland’s pressing with an offside trap. Germany, and Beckenbauer, emerged victorious, so while others fell in love with Holland’s Total Football style, Germany continued with their own”.

Germany, for those of you who have never looked at a map, is not an island. Neither is the Netherlands, and those Dutch ideas spread across Europe quickly. Ideas about vertical compactness in pressing were adopted in Italy, with Arrigo Sacchi creating a new kind of “post-Cruyffian” style. Cruyff himself moved to Barcelona and obviously had a huge impact there. By the end of the 20th century, essentially every top European nation had embraced some form of Sacchi-esque zonal marking with a back four (though England came to it a different way) except Germany.

Ralf Rangnick sought to change that. He played a heavily Sacchi-inspired compact back four system that broke all the rules of German football. He and fellow travellers, most successfully Jürgen Klopp, pioneered a new model of football in the Bundesliga. In the 21st century, you’re far more likely to hear people talk about gegenpressing than libero. Germany’s success as a country comes from always looking forward and reinventing itself without past dogmas. All of this filtered through to the national team, with Joachim Löw also believing in the modern and attacking tactics emerging from the country.

Things had transformed at youth level, too. After the disastrous performance in Euro 2000, Germany set about rebooting its academy programmes with a much greater emphasis on technique and tactical intelligence. According to Honigstein, all but two members of Germany’s squad had matured under this new academy approach, radically altering the style of football the national team might play.

German football was innovative and modern. At club level, it was earning a reputation for being the best in the world, all but confirmed in 2013 when Bayern Munich beat Borussia Dortmund in the Champions League final. German football stunned the world in the first legs of the semi-finals that season, as Bayern destroyed Barcelona 4-0 on Tuesday, then Dortmund dismantled Real Madrid 4-1 on Wednesday. Spanish football had been the standard bearer at both club and international level by a huge margin. To be good at football at the start of the 2010s was to be Spanish, even if it was driven by Catalans who wished they weren’t. In the blink of an eye, the balance of power had completely shifted.

But above all, German football wasn’t just new and good. It was cool. The games were fast and exciting, set to the soundtrack of highly passionate fans in state-of-the-art grounds. Teams were tactically sophisticated with a sense of identity running all the way through the league. The clubs were fan-owned, promoting a sense of solidarity and ownership of the working man’s game. German football represented everything English football wasn’t.

All of this put Germany in the perfect spot to win the World Cup. There was just one problem: fitness. Ilkay Gündoğan, who had been one of the best midfielders in Europe, missed almost the entire 2013-14 campaign and had no chance of making the tournament. Mario Gómez – not a player of the same quality but an important option in offering something different – similarly missed most of the season and didn’t have a shot at the World Cup. The biggest blow, though, was Marco Reus, internally “considered Germany’s most important player in the final third” according to Honigstein. Then you add the players who were theoretically ok but turned up to the preseason training camp well short of their peak fitness. Manuel Neuer was nursing a shoulder injury he picked up in the DFB Cup final at the end of the season. Philipp Lahm’s ankle was in terrible shape, requiring treatment from doctors during the training camp. Sami Khedira had ruptured his cruciate ligament less than a year earlier and still didn’t look like he had fully recovered. Bastian Schweinsteiger had been dealing with tendonitis for a while and, in truth, never regained his 2012-13 form. It would be impossible for Löw to pick a strong side that was completely fit. The heat of Brazil would also be far beyond anything the players were used to growing up in Germany, prompting Löw to play a less demanding counter-attacking style.

The mood at home was very pessimistic with the shape of the players coming into the tournament. They didn’t have an easy opening fixture to ease them into it. They would be playing Portugal in Salvador, situated in the hotter North East of Brazil. Portugal obviously had Cristiano Ronaldo, 29 years old and at the peak of his powers. The Portuguese made a mess of qualifying, needing to beat Sweden in the playoffs to book their ticket to Brazil. But this was still a serious team that should pose Germany problems.

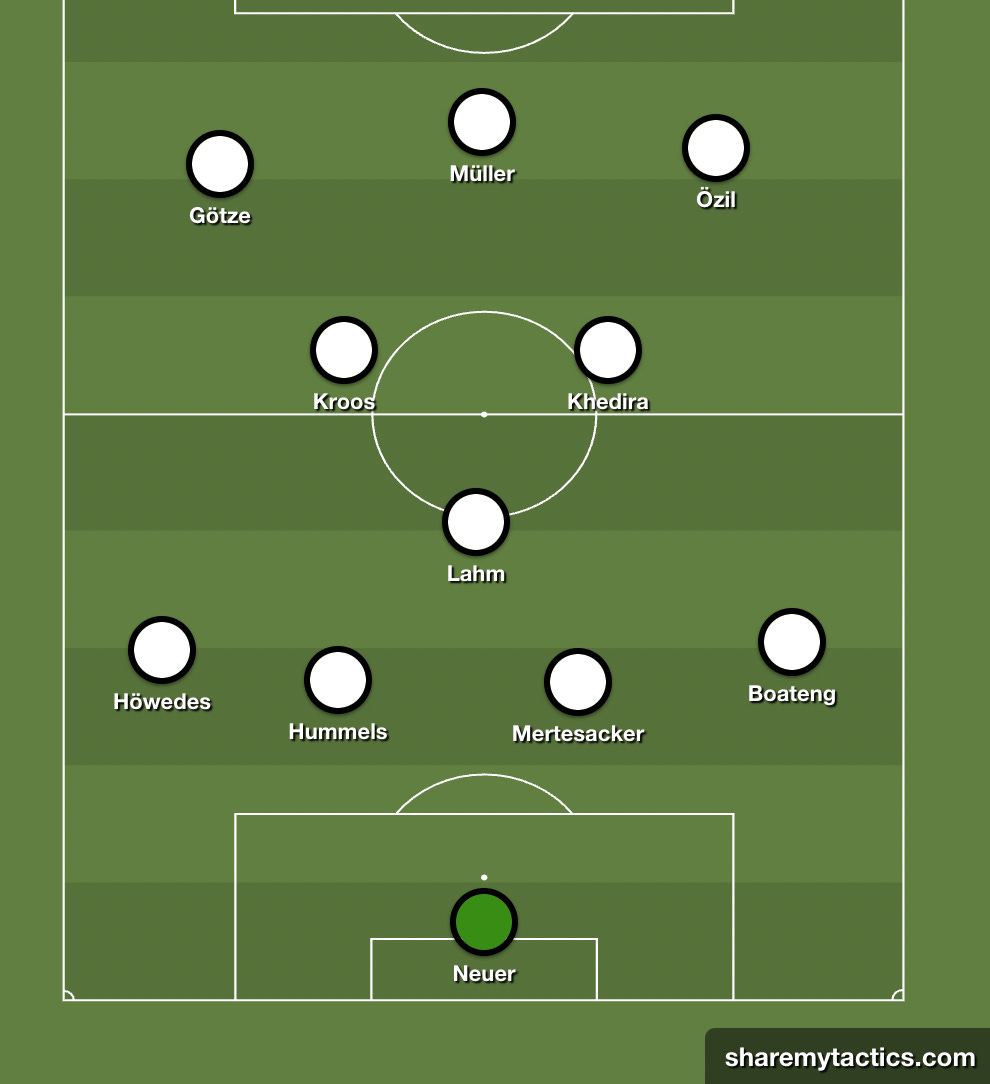

Löw had decisions to make. Neuer was deemed fit enough to start in goal. Nominal right back Lahm, captain and key player of this team, had spent the past season playing as a defensive midfielder under Pep Guardiola at Bayern. With questions about Schweinsteiger’s form and fitness, Löw opted to play Lahm deep in midfield. That meant moving centre back Jerome Boateng, who had played so well all season, out to right back. Per Mertesacker – an outstanding defender in his own box but a worry in open space – partnered Mats Hummels at centre half. At left back, Erik Durm was never completely trusted by Löw, so natural centre back Benedikt Höwedes started there. Yes, that’s right, four centre backs. It didn’t sound like liquid football. Khedira, someone Löw definitely trusted even when not fully fit, played alongside Lahm in midfield.

In an ideal world, Löw knew what his front four would look like. Marco Reus would play on the left, cutting inside with his direct running. Thomas Müller would do what he does best on the right, interpreting the space and popping up exactly where Germany needed him. Mesut Özil would be the star number ten, drifting around and linking everything together as he does at his best. Mario Götze, the star in the making, would play as a false nine.

But we didn’t live in that world. Presumably, because he felt the team needed a little more control due to fitness shortcomings, or perhaps because no one else could offer the same quality as Reus, Löw picked a third central midfielder in Toni Kroos. He instead went for a narrow front three. On paper, it was Özil on the right, Götze on the left and Müller upfront, but in practice, they interchanged frequently. This wasn’t quite the German lineup anyone expected.

It didn’t take long to settle those German nerves. 11 minutes into the game, João Pereira clumsily brings down Götze in the box. Thomas Muller smashes the ball into the bottom left corner and Germany are up and running. From there, they didn’t have to work very hard. Without the ball, they generally sat deep and soaked up pressure, trying not to tire themselves out by pressing hard. When they had the ball, Portugal’s structure didn’t do much to nullify Germany, and they could move the ball through midfield nicely.

After half an hour, Mats Hummels leapt over everyone to meet a Toni Kroos corner and make it 2-0. All too easy. Then it got much easier. Noted kind gentleman Pepe decided to headbutt Müller and earn a straight red. I have no idea what he was thinking, but it ended the contest. Kroos put a lovely ball into Müller to make it 3-0 just before halftime. In 45 minutes, Germany had gone from pessimism to jubilation.

The second half was predictably pointless. Germany were happy to just keep the ball and run the clock down, while Portugal wanted the nightmare to end. Müller got his third after a well-worked sequence, and the world had lost interest. Germany had started the World Cup with a bang in the first half and that’s what mattered.